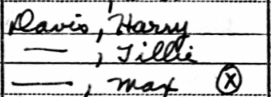

Here is my grandfather with his parents in the 1940 census. What do you think his mother’s name is?

Here is my grandfather with his parents in the 1940 census. What do you think his mother’s name is?

Ancestry says it is Jillie, but I know it is Tillie, my namesake. Amusing, right? In fact, Ancestry is so sure of its reading that it listed two Jillies on this one page alone!

As is now well-known, Ancestry relied upon vendors in China, Bangladesh, and the Philippines to index the 1940 census in just four months, finishing Friday (vs. 9.5 months for 1930). Unfortunately, not only are the indexers not native speakers of American English, the majority aren’t even native readers of the Roman alphabet. Comparisons of Ancestry’s outsourced index with the slower FamilySearch volunteer effort conclude exactly what you would expect — 23% vs. 12% inaccuracy on Carringer, Seaver, and McKnew in California; 12% vs. 2% on Alonzo in Utah.

The foreign indexers were trained via handwriting samples with mixed success. The Palmer-style script most 1940 census-takers used shows that capital J’s and T’s look quite different (unless you confuse script with block letters, which this census-taker clearly was not using). Better training might have caught this error.

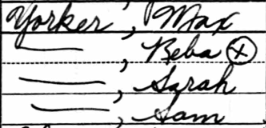

Beba is a real name–so sayeth Ancestry!

But no amount of training can fix the underlying problem: a lack of cultural awareness. Lifelong Americans know that Tillie is an old-fashioned name, and Jillie at best a rare, modern nickname. This aggregation of name data proves the name Tillie was extremely popular in my ggm’s day (she was born c. 1890). Jillie, on the other hand, never appears, Jill doesn’t come into use until the 1920s, and Jillian the 1960s.

Even had the indexers cross-referenced such data, they would still fail on unusual and foreign names. There’s just no substitute for a lifetime of passively absorbing a culture’s naming conventions. Even FamilySearch’s American indexers do a poor job indexing the New York City records of my Eastern European ancestors, because cultural familiarization happens on a much smaller scale than country or language. Names that are obvious to me frequently confound their amazingly generous volunteers.

So, the problem isn’t as simple as outsourcing vs. on-shoring. The bigger issue: in neither case — Ancestry or FamilySearch — does the makeup of the indexers match the ethnic diversity of the people whose names they’re deciphering. Ancestry wanted low cost/fast turn-around, and FamilySearch the speediest volunteer recruitment, but in both cases they were short-sighted: a shoddy index doesn’t convert casual visitors, since bad search results discourage newbies and frustrate experts. My cousin abandoned her free trial after Ancestry didn’t return our great-grandmother, Fannie Yorker (found under Marker — enumeration district address searching is tedious!). And I never use FamilySearch because time and again I get misses where I get hits elsewhere.

Until our indexing methodologies are more culturally aware, we aren’t going to raise our success metrics across the board. The increasingly diverse community of genealogists needs its indexing organizations to brainstorm substitutes for our own instinctual familiarity with our communities’ naming trends.

Follow

Follow

I found “Gillie” in Kansas in place of Tillie.

Wow, who knew this was such a tough name!