“Who lives, who dies, who tells your story?” The closing words of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s sensational musical Hamilton, these questions haunt both characters and audience from the moment they’re introduced in the first act. In the final scene after Hamilton’s untimely death, they receive a poignant answer: his wife, Eliza, who devoted the fifty years of her widowhood to shaping his legacy. As a family historian I find it awkward to wrap this question around someone whose story has been continually told, however imperfectly, when we are working to bring attention to the forgotten, but not inconsequential experiences of our families.

But Miranda has taken up this challenge, too. His first musical, In the Heights, provides a more universal answer to the same question by dramatizing the struggles of his own community, the Latino residents of the barrios of Upper Manhattan. Heights’ main character is Usnavi, a young bodega owner in Washington Heights, who doesn’t know where he fits – New York City, where he lives, or the Dominican Republic, which he left as a baby? Trying to hang on in a city squeezing them out, the characters of In the Heights are the opposite of the historically hyper-aware Founding Fathers of Hamilton. They feel powerless. And yet, Usnavi’s final revelation about his obligation to his community is not so different from Eliza Hamilton’s determination to ensure her husband’s legacy:

Yeah, I’m a streetlight!

Chillin’ in the heat!

I illuminate the stories of the people in the street

Some have happy endings

Some are bittersweet

But I know them all, and that’s what makes my life complete

And if not me, who keeps our legacies?

If not us, who keeps our legacies? Yes, in a small way, many of us have a sense that we are fighting apathy and forgetfulness in our own families when we reconstruct our family history. But my concern is a larger one, best articulated by Henry Louis Gates in an interview I quote often:

All historians generalize from particulars. And often, if you look at a historian’s footnotes, the number of examples of specific cases is very, very small. As we do our family trees, we add specificity to the raw data from which historians can generalize.

So when you do your family tree and Margaret Cho does hers, and … Wanda Sykes and John Legend … we’re adding to the database that scholars can then draw from to generalize about the complexity of the American experience. And that’s the contribution that family trees make to broader scholarship.

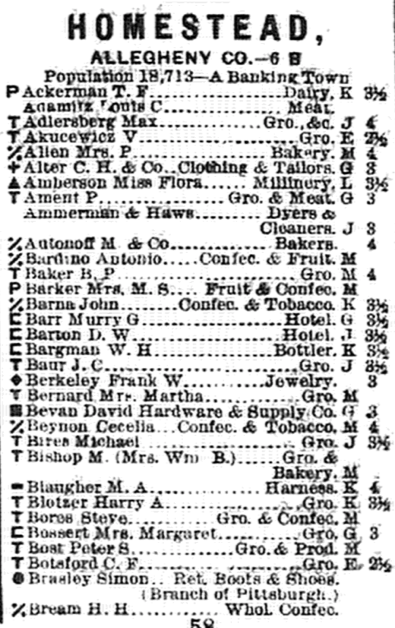

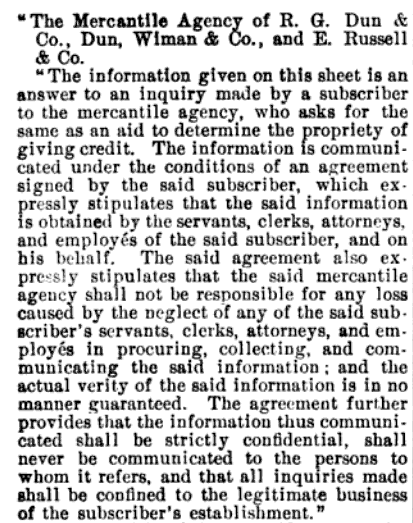

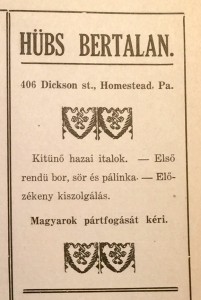

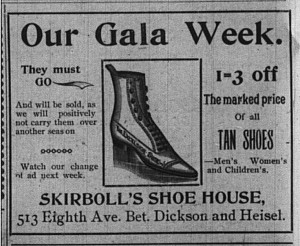

Illuminating our family’s past adds to the broader scholarship on the American experience when we recognize the public value of our private work. All our discoveries, at the very least, “add specificity to the raw data.” Plenty is known about the Jewish community on the Lower East Side, for example, but the work I did tracing my Davis ancestors through their frequent moves and changes in profession provides a detailed example of Eastern European immigrants who arrived relatively early, but never established stability. Our best work, however, can exceed this minimum threshold to open up whole new areas of the database no historian has discovered. I’ve experienced this personally during my current project to tell the story of my Hepps ancestors in the steel town of Homestead. In embarking on this research, I thought acknowledging their role in their hometown’s Jewish community was just one facet of the story. But, it turns out, the story of the Homestead’s Jewish community is the one that was missing all along. Homestead’s history has been written often, but never with an acknowledgement of the contributions of the town’s Jewish residents, and the history of Jews in America continues to neglect the narrative thread of small-town communities. Tracing the lines of my Hepps family’s descent led me to this twice-neglected dataset.

On one level, my research has been enormously satisfying. I’ve put the lives of my ancestors in context and come to thoroughly understand their stories. When Usnavi affirms, “I know them all, and that’s what makes my life complete,” I know I have earned that feeling of completeness, too. But what about the incomplete accounts historians have produced about the places and people that have become so dear to my heart? They were not excluded out of malice, but their absence leaves a hole in the record no one else sees and no professional historian is likely to take up. The void in my identity I sensed as a wondering child seems trivial compared to this one.

I hear “Who tells your story?” as a call-to-arms, because (to paraphrase another theme of the musical) if history hadn’t had its eyes on Hamilton, his wife’s efforts might not have been enough. As satisfying as the end of the musical is artistically, it’s not enough for me to know that this one man, Alexander Hamilton, has his legacy secure. Who will illuminate the stories of people who did not found nations? Who will write our ancestral communities back into the narrative? Everyday people like Usnavi. People like us.

Lin-Manuel Miranda as Usnavi in In the Heights

The untapped potential of family history lies between Hamilton’s “Who tells your story?” and Heights’ “I illuminate the stories.” History does not have its eyes on most of our ancestors any more than it does on Margaret Cho’s, Wanda Sykes’, or John Legend’s – or any more than it would on a woman like Usnavi’s adopted grandmother, a woman beloved by her neighbors, but anonymous to the world at large. “Abuela, I’m sorry,” Usnavi raps in the show’s closing moments when he decides not to return to the Dominican Republic. “I ain’t goin’ back because I’m telling your story,” he declares ecstatically, finally sure of his place. In the original cast album it’s Lin-Manuel Miranda who raps these words, and I hear in his voice not just Usnavi’s excitement, but his own: with his first outing on Broadway, he’s put the story of his people before the entire world. When In the Heights closed on Broadway, Miranda freestyled at curtain call,

One day you’ll be somewhere Midwestern

Somewhere chillin’ in some outer theater lobby

Some little high schooler’s gon’ be playin’ Usnavi!

So I want all a’ y’all to grab this —

That little white kid is gonna know what a Puerto Rican flag is!

His prediction has since come true, and his community’s flag has waved in the unlikeliest of corners. But what about ours?

“Will they tell your story? Who lives, who dies, who tells your story?” Through In the Heights, I’ve come to hear the ethereal last lines of Hamilton as transcending both Hamilton and his wife, to whom they are literally addressed. As the company sings these words, Eliza stands at the very edge of the stage, backed by the whole cast, all of them facing us, the audience, head-on. The previous three hours have shown us that history can be reclaimed and given a new relevance. Now they are asking, will we rise to the challenge?

Follow

Follow

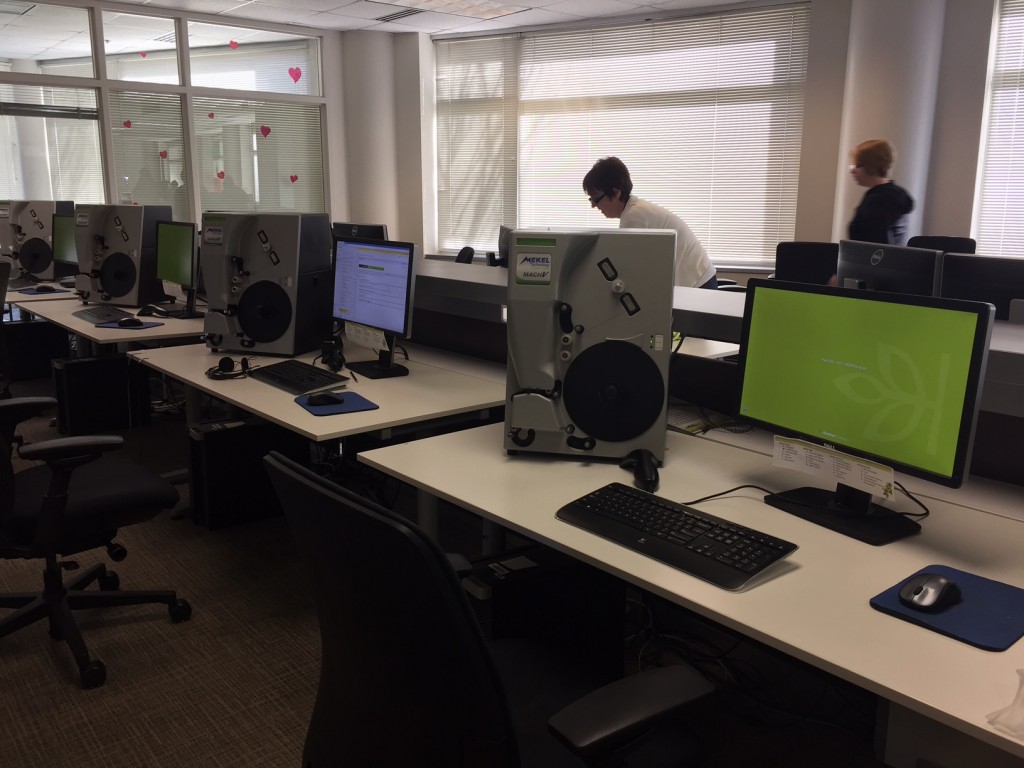

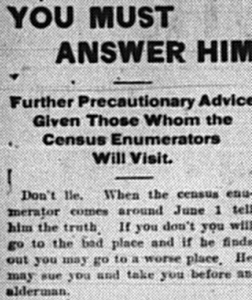

A trove of articles I’ve uncovered from The News-Messenger, the local paper of Homestead, Pennsylvania, sheds some light on these discrepancies from the perspective of the census takers in 1900. It’s clear that everyone understood the odds were against the enumerators to get accurate information, but the paper went to great lengths to ensure that “Homestead will not be found in the [class represented] as obstructing the endeavors of the enumerators to get the exact truth in the information they seek” (5/2/1900). It started by printing the census instructions several times to prepare readers with the list of questions they’d be asked and how to be sure of answering them accurately. In case the instructions weren’t enough, an often hilarious article from May 17, 1900 resorted to dire warnings:

A trove of articles I’ve uncovered from The News-Messenger, the local paper of Homestead, Pennsylvania, sheds some light on these discrepancies from the perspective of the census takers in 1900. It’s clear that everyone understood the odds were against the enumerators to get accurate information, but the paper went to great lengths to ensure that “Homestead will not be found in the [class represented] as obstructing the endeavors of the enumerators to get the exact truth in the information they seek” (5/2/1900). It started by printing the census instructions several times to prepare readers with the list of questions they’d be asked and how to be sure of answering them accurately. In case the instructions weren’t enough, an often hilarious article from May 17, 1900 resorted to dire warnings: