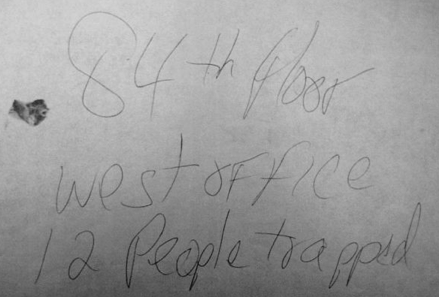

In response to last week’s 9/11-related post my sister sent me this article about the Scott family, who learned just before the ten-year anniversary how their father/husband really died:

“I spent 10 years hoping that Randy wasn’t trapped in that building,” Denise, 57, said Friday from a front room in her Stamford home with two of her three daughters, Rebecca, 29, and Alexandra, 22, at her side.

“I thought he was killed instantly,” Rebecca interjected.

“It was so close to impact,” Alexandra concluded.

In a steady tone, their mother explained the power of the note. “You don’t want them to suffer. They’re trapped in a burning building. It’s just an unspeakable horror. And then you get this 10 years later. It just changes everything.”

Last week I mused about how we genealogists use research and imagination to connect the few facts we have about a person into a coherent life story. But my sister reminded me that a life story is based more on the information we can pin down than the spaces we fill in. And however we reconstruct them, the narratives only hold so long as they aren’t disrupted by an unexpected discovery, like Randy Scott’s letter. Whether we actively research or merely make ourselves available, as Denise did, answers find their way back to us against the odds.

Marla is related to the Lieblings named in the letterhead

It happened to genealogist Marla Raucher Osborn when, during a visit to her ancestral town, she unexpectedly found physical traces her family left behind during the Holocaust, also in the form of scraps of paper, the poignantly normal vestiges of lives that were completely destroyed in an age of unprecedented madness. Randy’s letter was “tenderly preserved as it traveled from hand to hand and through time to reach” his family. Marla’s papers owe their survival to a school director who understood what he found when the school was renovated and trusted that one day a recipient would appear. She reflects:

So, what remains of a life after that life has ended?

Here is my answer. That physical traces can be found—sometimes by pure chance, or by being at the right place at the right time; sometimes by persistence and repetition and by gaining the trust and friendship of those who work the archives, run the libraries, conduct the Church services, or are local historians or personalities. In all cases, these traces, whether they be records, shreds of paper in a box, notes from an oral history, or forgotten headstone fragments, are like a muffled voice calling out to you from far away, saying, “I was here. I too had a life that was real and meaningful.”

Marla left Ukraine “feeling the ties of the past—ties that now bind [her] forever to the place” her family called home for generations. Even Denise found comfort that her husband’s message, now in the 9/11 museum, “tells people the story of the day.” For them to hear the muffled voices just a bit more clearly justifies the years of effort or waiting.

There are so many more traces out there, waiting to be found, from the lives that matter to each of us. That’s what I always tell friends who are on the fence about starting their family’s genealogy: you will be surprised by how much you’ll find, even for the most seemingly hopeless of cases.

Follow

Follow

Bravo again!

And a hearty thanks, too!

Thank *you* for your inspiring article and beautiful words!