Eager Americans tearing down the Union Jack (nailed up to a greased flagpole by the petulant Lobsterbacks) on Evacuation Day. In subsequent commemorations boys would compete to perform this feat themselves!

In the U.S. late November has long been defined by the Thanksgiving holiday and its message of gratitude. But in New York for the first half of our history the defining holiday of November commemorated not this 1621 Pilgrim harvest feast, but an arguably more seminal moment in the country’s establishment: the long-overdue evacuation of the British from New York City in 1783, more than two years after the Revolutionary War’s last major engagement at Yorktown. It wasn’t just soldiers who evacuated on that day, though. 1,500 Loyalist civilians, the last of a months-long exodus that may have numbered 40,000, departed as well. We know how the story continues for the Patriots who built our country. But what of the evacuees, who risked everything simply for their desire to live under the same form of government that had been in place for generations?

Their story begins at the start of the war, when the British had conquered New York in August 1776. Shortly thereafter, a huge and mysterious fire destroyed much of the city. Of those who remained in town, those with Patriotic leanings were left in the slums of the “Tent City,” while British officers and prominent Loyalists occupied the choicest residences, regardless of ownership. As a result, after the British defeat at Yorktown in 1781, New York City was the most obvious destination for Loyalists from across the thirteen former colonies. But Patriot New Yorkers returned in droves, and the passage of 1783 Trespass Act gave them a legal pathway to make claim on properties utilized by Loyalists during the war years. Patriot claimants were even indemnified against counter-suits by known Loyalists! Add to the mix thousands of nervous African Loyalists, whose freedom was unclear, and an unknown number of bounty hunters, and you’ll understand how occupied New York City became increasingly chaotic as the peace negotiations in Europe dragged on.

An honorable Redcoat? Carleton freed the slaves who fought with the British and safely evacuated Loyalists.

After numerous brawls and a few coordinated attacks against the hated Tories, British General Sir Guy Carleton declared it his intention to protect the life and property of loyal subjects, and he wouldn’t relinquish the city until his job was complete. He helped establish a joint Board of Claims, the first in a long list of ways Loyalists would attempt to win reparations for their lost property over the next fifty years. He also remained steadfast against General George Washington’s objections to freeing the slaves who had run away from their owners when the British promised emancipation to any who would fight against the Americans. And during that last summer of the occupation, the British government gave free passage to Loyalists to other ports in the empire, primarily Canada — a promise that flabbergasted those in charge of the retreating military’s logistics! In the end approximately 40,000 Loyalists, including 3,500 Black Loyalists, were evacuated safely to Canada or Nova Scotia.

Washington’s triumphal entry into NYC on Evacuation Day.

All of this is a lot to take in! Americans who hated the Declaration of Independence…a New York teeming with enemy soldiers…our most heroic Founding Father tarnishing his reputation to keep men who risked their lives for their own freedom enslaved. Also unexpected for students of American history is the pride Canadians take in their Tory forebears:

United Empire Loyalist monument in Hamilton, Ontario. The accompanying plaque reads:

This Monument is Dedicated to the Lasting Memory of The United Empire Loyalists who, after the Declaration of Independence, came into British America from the seceded American Colonies and who, with faith and fortitude, and under great pioneering difficulties, largely laid the foundations of this Canadian nation as an integral part of the British Empire.

Neither confiscation of their property, the pitiless persecution of their kinsmen in revolt, nor the galling chains of imprisonment could break their spirits, or divorce them from a loyalty almost without parallel.

“No country ever had such founders — no country in the world — no, not since the days of Abraham.” — Lady Tennyson

Proudly Tory Shelburne, Nova Scotia, also the site of race riots against Black Loyalists in 1784. Half of this group took the opportunity offered by the British government to begin anew in Sierra Leone in 1792.

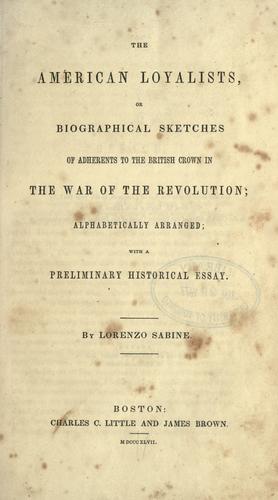

Loyalist genealogical associations began to blossom, particularly in Canada, with the 1847 publication of The American Loyalists, or, Biographical Sketches of Adherents to the British Crown in the War of the Revolution by Lorenzo Sabine, a New England businessman and politician with no familial connection to Loyalism. Coining the term United Empire Loyalists, Sabine invigorated descendents of Loyalists to honor their ancestors and acknowledge the hardships they endured. Sabine’s work is now regarded as a starting point in Loyalist genealogy. It gives the most attention to those prominent men who often managed to transfer their wealth and/or power from one imperial outpost to another: an example is Charles Inglis, the rector of New York’s famous Trinity Church and author of The Deceiver Unmasked; or, Loyalty and Interest United: in answer to a pamphlet entitled Common Sense (as in, Thomas Paine’s revolutionary pamphlet Common Sense), who became the first Bishop of Nova Scotia in 1787.

Loyalist genealogical associations began to blossom, particularly in Canada, with the 1847 publication of The American Loyalists, or, Biographical Sketches of Adherents to the British Crown in the War of the Revolution by Lorenzo Sabine, a New England businessman and politician with no familial connection to Loyalism. Coining the term United Empire Loyalists, Sabine invigorated descendents of Loyalists to honor their ancestors and acknowledge the hardships they endured. Sabine’s work is now regarded as a starting point in Loyalist genealogy. It gives the most attention to those prominent men who often managed to transfer their wealth and/or power from one imperial outpost to another: an example is Charles Inglis, the rector of New York’s famous Trinity Church and author of The Deceiver Unmasked; or, Loyalty and Interest United: in answer to a pamphlet entitled Common Sense (as in, Thomas Paine’s revolutionary pamphlet Common Sense), who became the first Bishop of Nova Scotia in 1787.

Today there’s a lot more you can read about these families, whether you are researching your own roots or fascinated by this lost chapter in U.S. history. Genealogists such as Gregory Palmer and Paul Bunnell have updated and vastly expanded Sabine’s work, taking more systematic and scientific approaches to tracking all Loyalists, regardless of economic circumstances, political stature, gender, or race. Between them they have mined tens of thousands of Loyalists claims and found evidence of Loyalist migrations to the furthest corners of the British Empire. Historian Philip Ranlet provides remarkable depth to New York loyalism in particular, outlining the continuum of these British subjects’ political activism, which ranged from passive obedience, to militant Toryism via regiments that weeded out disloyal neighbors and took on Continental soldiers (loyalist New York City troops alone made up four battalions!). Further complicating the range of Tory identities, Richard Ketchum argues that many New York Loyalists began as active reformers against onerous Parliamentary acts in the 1760s, but ultimately drew the line at full-fledged revolt. And Black Loyalists get special attention from James Walker, who researched their arduous journeys from the 13 colonies to Nova Scotia and onto Sierra Leone in a protracted effort to gain true freedom.

There is so much in this history that complicates the straightforward narrative we Americans are typically taught about the founding of our nation. Like Evacuation Day, Thanksgiving certainly comes with its own troubling questions — the harmony between Pilgrims and Native Americans did not last much beyond that one meal, as is well known — but regardless of which holiday we observe this week, nothing is more American than thinking critically about our history to make a better world. Let’s be grateful we live in a country where we can do so!

Follow

Follow

Excellent post! I am a United Empire Loyalist descendant (and, ironically, a Mayflower descendant) just embracing my UEL roots and exploring the history. I love your critical perspective.

Thank you for this perspective! I am a researcher who has encountered family historians that deny their Loyalist roots until presented with concrete documentation proving such. Why should we not “celebrate” our heritage under a different comprehension than before? I really appreciate your blog article as seen at Loyalist Trails newsletter.

Thank you for the excellent article. I come from Loyalist / Tory descent AND Patriot / Rebel descent, including one ancestor who started out as a Rebel but became a Loyalist. I have enjoyed studying the history of the period for many years. It was a period with many rights and wrongs on both sides of the dispute, but at the end of the day these were all just people with many different agendas, all trying to improve their lot in life. It is refreshing to see such a thought provoking article that tries to tell the story of the first American Civil War in the proper light.

Very well written piece of (objective) history. Thank you!

Pingback: Loyalties | The Chesney Household

Pingback: Loyalist Trails 2014-48 – UELAC