Since this year’s RootsTech wrapped up, there has been some grumbling amongst the techier attendees about the relative dearth of technical sessions this year compared to RootsTech’s early days. And yet, the conference drew by far its largest audience, showing that changes which troubled a minority appealed to the overwhelming majority. These conservations about RootsTech’s evolution got me thinking about whether there really is such a divide between genealogists and technologists. As a member of both groups, I’ve long seen an overlap in how good genealogists and good technologists work, because we’re all hackers.

Your first thought may be to bristle at the comparison. Hackers are evil geniuses who steal your emails, selfies, and credit card and social security numbers for fun and profit, right? Well, not exactly. For one thing, they’re hardly required to have genius-level skills anymore, with so many tools freely available and so many under-protected systems there for the taking. But more importantly, they aren’t always evil, either. Paul Graham, a well-known tech investor, articulates how most programmers would define the term:

To programmers, “hacker” connotes mastery in the most literal sense: someone who can make a computer do what he wants—whether the computer wants to or not… When you do something so clever that you somehow beat the system, that’s…called a hack.

—The Word “Hacker”

Graham goes on to explain that hacking predates computers, giving examples of people who cracked safes not to steal anything, but just for the curiosity of discovering how the device worked and the intellectual satisfaction of having solved the puzzle. “Show any hacker a lock,” he writes, “and his first thought is how to pick it.”

Some years ago I met Paul Graham and had to give him an example of something I hacked. My first thought was, who, me?! But I’m the textbook example of a goodie-goodie! I like to think I have as much curiosity as the next person, but I’d never dream of channeling it in such ambiguous ways.

And then I realized: I hack history every day! As a genealogist, the locks I pick aren’t on doors, safes, or firewalls — they’re on time itself. The system I reverse-engineer is the by-product of the fundamental human impulse to keep records of our existence. The lives of our ancestors intersected with these record-keeping systems — military, governmental, religious, fraternal — that took down their information long ago and are often still out there preserving it. A good genealogist knows how to find those intersections, and if the records of those intersections survive, s/he can provide answers others would consider irrevocably lost. A good genealogist makes the system give up its secrets. (And in case it isn’t clear, I present this analogy as someone who researches family history and writes code in equal measure.)

My uncle said to me after his parents, my grandparents, passed away, “I guess we’ll never know where their parents came from,” and within a month I had a pile of records — primarily censuses, ship manifests, and bank records — documenting the immigration stories of all of four of his grandparents, my great-grandparents. If you’re a genealogist, you know that this research isn’t impressive. But my uncle’s eyes welled up when he read stories he had given up on ever knowing. Rediscovering my family’s immigration story — towns, dates, even original names that I, too, had once believed lost — was the moment I gave myself up to genealogy forever. I cracked the system once. I needed that fix again.

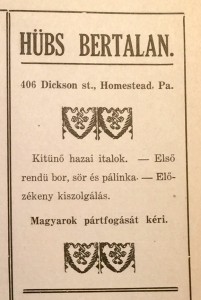

This ad, in a program for a dramatic evening organized by a local Hungarian group, is the only one I’ve ever found for my great-grandfather’s business after years of searching. How could it have been so profitable with no advertising?! “I can’t imagine how you possibly found this,” my father wrote when I sent this ad to him. (Source: Archives of the Carnegie Library of Homestead, Collection No. 22, Box 22, Folder 4.)

Last summer a cousin sighed, “I wish I could know how our great-grandfather made his fortune.” Naturally his rumination became my challenge. Like any hacker, my natural impulse is to prove I can pick this lock, too, but it’s a much harder one. I had no easy clues to start with, no letters, journals, or bank statements someone threw into an attic. And the kinds of genealogical records that opened doors before turned up little this time; his ship manifest is missing, the pivotal 1890 census is gone, and the town’s city directory, by its own admission, bothered little with poor “Hunkies” like my great-grandfather. But they revealed just enough for me to see the shape of the story I must fill in. Somehow my great-grandfather went from delivering liquor for a local wholesaler in the 1890s to building and running his own hotel in the early 1900s.

So off I went, considering every possible way such a man would have intersected with the record-keepers of his time. Old newspapers tell me he appeared in Pennsylvania’s annual license court for a judge to decide if he was fit to sell liquor; does the county have transcripts recording his testimony? Deeds show me when he bought the land for his hotel, and Sanborn maps suggest the timeframe when the building went up; does the borough have building permits? Tax records? Voter rolls? What about records from before he made the leap — peddling licenses, bank loans, personal loans, credit reports? The more I press on, the more I see that — to paraphrase Daniel Mendelsohn — the records are not so much lost as waiting. I ask clerks to show me ledgers covered in dust and archivists to escort me into rooms closed to the public, and I wind my way, literally, through miles of microfilm. Through sheer dint of effort, I will make the past give up what secrets it retains. I have already gleaned some; ’til I got started, no one living even knew my great-grandfather had started as a teamster. This discovery is satisfying, but it is only the beginning.

What we do as genealogists isn’t always intellectually demanding. There is a tremendous amount of brute force in a reasonably exhaustive search (though there is in programmatic hacking, too, only one can automate such tasks). But just as surely as there is artistry to hacking (see Graham’s essay Hackers and Painters), there is artistry in knowing how to dance from record to record. You have to know how to frame a question clearly and precisely. You have to know how to determine what sources are out there. You have to know how to bend the sources you find to your will. In Jewish exegesis, there is the p’shat, the surface meaning, and then three deeper levels of meaning. Genealogical records aren’t as many-layered as scripture, but if you can’t get beyond the p’shat, you’ll miss most about what a record is telling you — and more importantly, where it is pointing you next. Part of moving beyond the p’shat is having a sufficient command of the period you’re researching. Even this most indigenous aspect of historical research has an analog in hacking. “Great hackers can load a large amount of context into their head,” Graham writes, “so that when they look at a line of code, they see not just that line but the whole program around it.” Similarly, a great genealogist doesn’t see a record in isolation, but as the product of the historical circumstances that created it and link it to other such records. Though we genealogists push ourselves through long periods of semi-engaged searching ’til we find the needle in the haystack, those periods are framed by a creative, considered approach not unlike how a hacker assesses his or her mark.

In Star Wars the rebel alliance discovered that the Death Star had one small, unprotected opening through which they could destroy it.

Genealogists and hackers are united in their delight in cracking seemingly impenetrable systems. So many of the qualities Graham articulates about great hackers are what I see in the best genealogists I know — a love for their work, a marked preference for interesting problems they can learn something from, and a special ability to focus. Both groups take on inherently imaginative work, engaging in it cyclically based on shifting levels of inspiration. In sum, we demonstrate a similar work ethic as we pick at our respective locks, trying to open doors others consider impossible to budge.

You may or may not see yourself in this analogy… yet. I pointed out at the start that today plenty of wannabe hackers lack the qualities Graham articulates — script kiddies, this lesser group is called, after the scripts they run without understanding just to see what havoc they can wreak. Here, too, I see an analogy with genealogical research. Digitization has come so far that it’s easier and easier to fall into the trap of being a “search kiddie,” just typing your ancestors’ names into online databases to see what’ll come up. Script kiddies are beholden to the scripts better hackers share; search kiddies are beholden to the records others choose to put online. Sometimes those records get you where you want to go; they were more than enough for me to give my uncle the answers he was looking for. But if I had believed those records were the beginning and end of what remains from the past, I’d have believed my great-grandfather’s early years in the U.S. were entirely lost.

There’s one more quality about good hackers that applies equally to good genealogists: a sense of wonder. You have that, too, wherever you are on the genealogy learning curve. The wonder about the past that got you started in family history is the same wonder you need to apply to researching more creatively. There is much more information out there than you realize, waiting for you to discover it. The heart of hacking is “[doing] something so clever that you somehow beat the system,” so embrace your innate curiosity and start hacking those historical records. For many of your most pressing questions, it is not too late to find answers.

Follow

Follow

I love the way you’ve expressed this obsession of ours to get to the bottom of the problem, make discoveries, and “crack the safe”. We may each approach it slightly differently but we acquire new skills and apply them, whether we use tech tools or not. I like that acquiring genie-tech helps keep me rooted in the 21st century’s challenges.

Thanks so much! 🙂

And you make a good point when you say “whether we use tech tools or not” — while genie-tech keeps us rooted in the 21st c., ironically some of our best discoveries come when we leave all the technology behind and dig in the corners where digitization hasn’t hit yet.

Absolutely! I’m obsessive about offline resources…one of my hobby horses 🙂

I don’t drink, do drugs, or run until I get that “high” I’ve heard about. But I do try to do genealogy or/and family history, and I do get what I think is a ‘buzz’ when I am able to find something that seems to be new to the world. I think part of the thrill is just acknowledging that I’ve done it, but definitely most of the thrill is in filling in another blank spot in the puzzle of my ancestors. I am very low tech but I am still doing a lot more, and finding a lot more, than I’d ever dreamed possible.

Thanks so much for for your comment! I love how you phrase it — when you “find something that seems to be new to the world.” That’s the best buzz, isn’t it, that utter shock and disbelief that (a) you did it!, and (b) does anyone else even know this amazing/crazy thing you uncovered?!

And don’t apologize for being low tech — my best discoveries BY FAR are the ones I made using the lowest tech means. 🙂

Great piece. In the beginning you wrote of “some grumbling amongst the techier attendees about the relative dearth of technical sessions this year “. This got me thinking. Technology becomes part of everyday life so does not require “sessions” to teach us about it. Imaging going to a session on how to use a photocopier or send a fax. Just would not happen now days. But these are things we learnt or read up the instructions on. What is better about technology today is that many developers try to make it so much more user friendly so that we do not even need lessons or instructions. Technology will always be advancing and integrating in our lives even when we are not conscious of it happening. Fran

Thoughtful comment, Fran! You make a great point from the perspective of a consumer.

From the perspective of the developers, there used to be sessions about the underlying technical infrastructure — software, databases, data specifications, transfer protocols — that genealogy developers must master to deliver products to consumers. A lot goes into making genealogy products as user-friendly as you describe! 🙂 I believe that is what the techier folks are missing from RootsTech.

Yes when the audience is from a variety of backgrounds and needs it can be difficult cater to all of their requirements. Being to diversified with content can also create problems in that there is then not enough “good stuff” for an individual to warrant their attendance. I think that Rootstech does well catering to many needs as shown by the numbers that attend.

Yes, totally! Hopefully other conferences can fill whatever voids left by RootsTechs’ shift, since they’re clearly onto a winning formula! BYU’s long-established Family History Technology Workshop is one possibility. The brand-new Gaenovium is another.

Pingback: Friday Finds – 02/27/15

Tammy,

I want to let you know that your blog post is listed in today’s Fab Finds post at http://janasgenealogyandfamilyhistory.blogspot.com/2015/02/follow-friday-fab-finds-for-february-27.html

Have a great weekend!

Thank you so much! I’m glad you enjoyed reading it, and I really appreciate your sharing it with others!