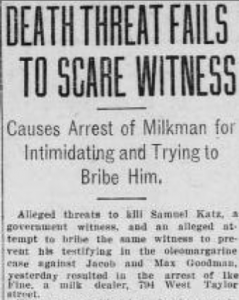

If you’re in business today and considering partnering with another company, you might rely on Dun & Bradstreet to acquire “commercial data…on credit history, business-to-business sales and marketing, counterparty risk exposure,…lead scoring” and other business metrics for “more than 235 million companies across 200 countries worldwide.” You might be surprised to discover that such a modern-sounding company, addressing what seem like contemporary business challenges, dates back to 1841, when the company’s founder “[created] a network of correspondents who would provide reliable, objective credit information to subscribers.” (source) The company’s name became R.G. Dun & Co. in 1859 after an ownership change, and a merger with a competitor produced Dun & Bradstreet as we know it today. Despite all the name changes, the company’s mission has remained remarkably consistent.

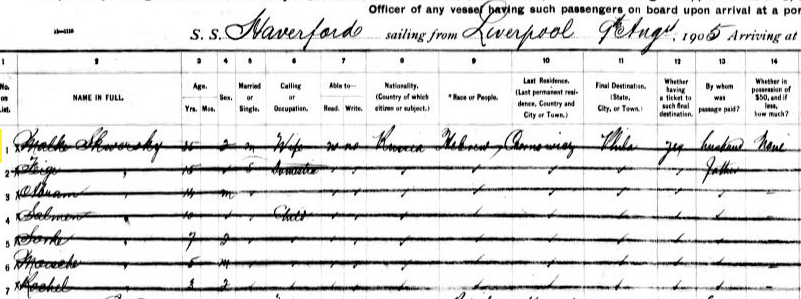

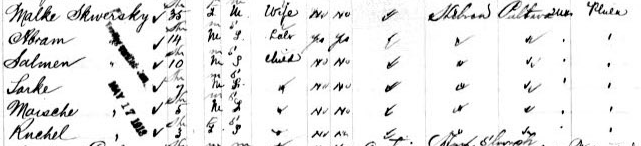

What has changed is the size of the database and the nature of the companies included. In the early 1900s, when the database of ~1.5 million merchants first included my great-grandfather, it reflected a time when most businesses were synonymous with their proprietors, making researching the businessman and researching his business nearly identical activities. From this period two sets of historic R.G. Dun & Co. records are accessible to researchers, making it possible to gain far more insight into our ancestor’s business activities than the usual names and professions we find listed on genealogical records.

Reference books

The first set of Dun records are reference books which were published by a subsidiary called The Mercantile Agency, which maintained offices in many commercial cities. Local agents worked to identify all the “merchants, manufacturers, and traders” of the vicinity in order to “[supply] information in detail as to the antecedents, character, capacity, and credit of Business Men throughout the civilized world.” Four times a year, they published an updated list of all these men (and sometimes women), organized by city and state and coded with their business type and credit rating.

1880s R.G. Dun & Co. reference books at the Library of Congress

A fairly complete run of these reference books is available at the Library of Congress, covering 1859-1966. Most of the books are only available as physical books, which must be requested in advance, but the 1900-1924 run is on microfilm, with two reels per edition, or eight reels per year, all of which are stored on-site. If you know the city and state in which your ancestor was located, it is easy to wind to the section for that state, then to the town within that state, and then scan the town’s list for your ancestor’s name. In this way I was able to pinpoint one great-grandfather’s entry into the liquor business and trace another great-grandfather’s relocation from one state to another. For those ancestors I can’t identify when they lived where, using the books to solve such mysteries would be tedious-bordering-on-infeasible. But they could solve these mysteries if only they were scanned and OCR’ed. Federal censuses come every 10 years in the U.S., city directories are at best annual, but these books, remember, came out four times per year! Imagine the kind of granular data available to you if your ancestors were included!

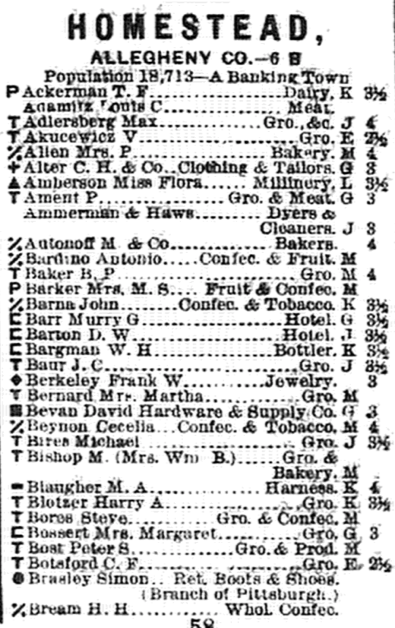

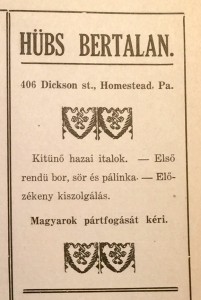

The question you may be asking yourself, then, is whether your small-time merchant, manufacturer, or trader ancestor warranted inclusion? And the answer to this question is what I find most remarkable about these books — yes! I reviewed the microfilm from 1900-1914 for Western Pennsylvania, and saw even the tiniest of towns listed with their one or two local merchants. For Homestead, PA, where I had already compiled merchant lists from censuses, city directories, newspaper records, and synagogue records, I saw that these books covered even the smallest mom-and-pop shops. These records are not “best of” compendiums; they aimed and succeeded in being truly comprehensive.

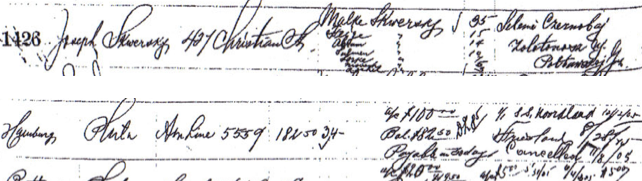

Partial list of Homestead merchants. (Source: The Mercantile Agency Reference Book, June 1913. Vol. 181, Part 2. Scanned from the microfilm at the Library of Congress.)

While the businessmen lists appear to be objectively complete, the subjective nature of their credit ratings makes them less trustworthy. Having such familiarity with the businesses of Homestead, I was surprised to see that merchants held in high regard by the town’s paper, or whose other activities suggested personal wealth, were given low credit ratings. It’s clear that one’s rating and success do not correlate in an obvious way.

Agent reports

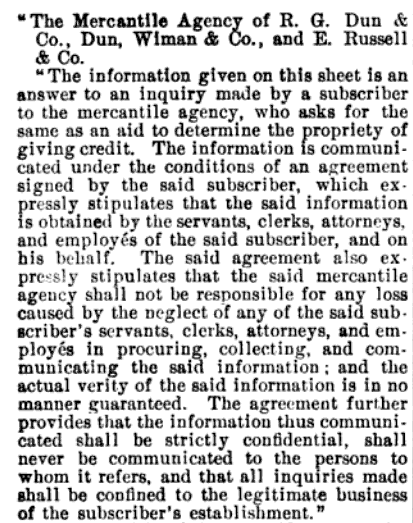

How the agents arrived at the credit ratings is illuminated by the second set of R.G. Dun & Co. records. These are the agents’ detailed field reports with the information they collected about each businessman they researched. Another businessman or bank could order this full report if they needed to know the specific information that went into the credit rating printed in the reference book.

“The information given on this sheet is an answer to an inquiry made by a Subscriber to The Mercantile Agency, who asks for the same as an aid, to determine the propriety of giving credit. … the information thus communicated shall be strictly confidential; shall never be communicated to the persons to whom it refers…” (source)

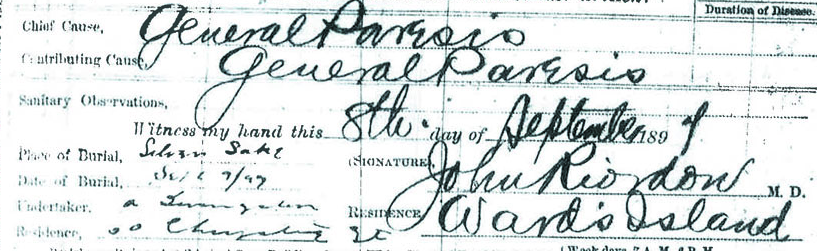

These records are much harder to get a hold of. Very early handwritten records from 1841-1891 are available at the Harvard Business School library, but they are off-limits to genealogists. No one I’ve spoken to, neither reference librarians, nor the current-day D&B employees I’ve contacted, knows where the later, typewritten records are.

The early agent reports consist of handwritten volumes divided by state and indexed by the last and first names of the people included. It proved too challenging a system for me to review all the merchants of Homestead or even Western Pennsylvania as I had intended, but I was able to look up the individual merchants whom I had previously identified from other sources. The entries I read were fascinating and colorful. Somehow the agents gathered detailed information about whether each businessman paid his bills on time or owned real estate, what were the his character and net worth, and how he and his family members were connected to each other’s businesses. Multiple entries were recorded over many years, tracing the cycle of a person’s fortunes. All of these notes served to answer one question: If you loaned this person money or sold him goods on credit, what was the risk you won’t get your money back? For example:

- About a peddler in 1882, “Does a pretty [fair business], but not in a position to be sued if not disposed to pay…Not in the market for credit. Cash only suggested. Could not force collections. Said to have means but in such shape could not attached.”

- About “a peddler traveling with his pack upon his back” in 1882, “He has a [modest] line of credit at home. Is considered honest and manages to do a fair [business] is inclined to be a little slow of late. He is not thought to be worth much and should buy sparingly.”

- About a tailor in 1883, “His financial responsibility limited and the trade in some instances go cautiously, selling him on sharp 30 days.”

Not all were assessed so critically, though most of the small-time merchants I was researching were. A couple more positive examples:

- A man with a highly-regarded feed store in 1884, “is spoken of as a very reliable close going man. Strictly honorable in all his bus. dealings. Owns property in the 19th ward. Does a very snug [business]. Pays his bills promptly. Making money and knows how to take care of it. [Estimated worth] 5 to $8,000.”

- About a wholesaler in 1881, “In [business several years] – [should] be [doing] well + [thought] to hold his own at least. Active + [attentive,] [regarded] honest. His father failed some [years] ago + it was the impression that he was connected with it – this had the effect of impairing his [credit]. We hear no complaints as he was credited [small amounts] by some here. Is [worth] at least 2-3 [thousand] $ now worthy [modest credit], though a little caution [should] be used in granted large [credit].”

Some entries betray the latent biases of the period. My particular interest was in researching Jewish merchants, who were easy to pick out since agents took care to note this characteristic — sometimes benignly (“a Jew”), and other times insinuatingly (“a very close Jew”). One merchant, agents noted repeatedly, was called “Jew John” by his neighbors (his name was Leopold). “Not in favor here,” one agent summarized about him. Though it’s impossible to know just what put the agents off men like “Jew John,” the cumulative effect of their field notes gets at a certain reluctance amongst by the establishment to trust people not like themselves in business matters. And yet, as difficult as such raw material is to read with its transparent racial, religious, nativist, and even socioeconomic biases, it certainly adds insight into the challenges such men faced in trying to overcome these prejudices.

(Researchers are not permitted to photograph these books, which is unfortunate, as the entries are written in difficult handwriting with numerous abbreviations (all of which I replaced in my transcriptions for readability). Please forgive any errors. You can see a couple photographs of other Dun records here, if you’re curious.)

Research opportunities

Unfortunately, I am not yet able to complete the circle of research. While I have the credit ratings for the Homestead merchants for whom I’ve been able to compile detailed biographies, I haven’t been able to find the internal reports for anyone from that time period, Homesteader or otherwise. Do the internal reports match up with the pile of evidence I’ve collected from other sources? If not, why? Is it because the agents, coming from outside of the community, couldn’t truly penetrate the complex social dynamics that made it possible for men who seemed like the Other to gain acceptance? Is it because the agents only interviewed men like themselves, who had a vested interest in raising the status of men in their own networks and lowering the status of their competitors from other backgrounds? Is it because by ignoring informants from marginal groups, the agents overlooked the role of ethnic support systems in advancing the members of their own group?

These elusive, later agent reports are a critical missing piece in my research. Despite years of looking for untapped sources, I have not been able to find anything even remotely comparable to the unfiltered assessments of the early agent reports. I crave this level of insight into how the community I am researching was really regarded by outsiders.

So — my immediate goal is to interest someone, anyone in digitizing the printed, quarterly reference books. Their genealogical value is significant, and their layout makes them well-suited to search engines already commonly used. Update January 2022: Mission accomplished! The Library of Congress just posted the digitized volumes for 1900-1924 (the microfilm portion). The earlier years, 1859-1899, should be added starting in spring 2022. Thank you to Natalie Burclaff at the LOC for championing this project and to everyone else at the LOC who made this happen!

My secondary goal is to continue to dig for the internal reports, which I believe are still held by Dun & Bradstreet. Selfishly, I need them to complete my personal research into the merchant class of Homestead. But if Dun & Bradstreet were open to donating their reports to an archive with fewer research restrictions attached, the unique observations they record could allow family historians to see their merchants ancestors from a new angle. Wouldn’t you love to know if your ancestor made his fortune by selling “[dry goods] + made up Underwear…on the [installment] plan” to “‘Fancy Women’ [hereabouts]?!”

Further Reading

These records have formed the basis of many fascinating and remarkably in-depth studies. Here are a couple on early Jewish merchants that make me salivate over the possibilities of what these records might contain for the community I am researching.

Follow

Follow

When I found my great-grandfather in the

When I found my great-grandfather in the