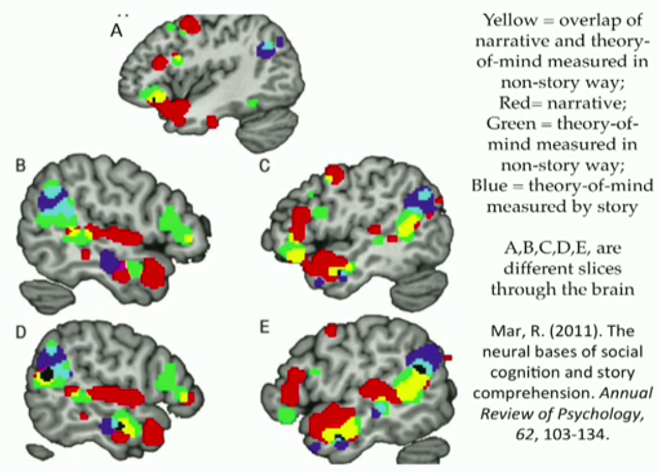

In the picture above, red is your brain on story. Green is your brain thinking about social situations. And blue and yellow represent overlaps of the two. The point of the picture is that roughly the same regions of your brain are active when you read stories as when you interact socially. Any questions?

…?

Haha, yes, we’re only at the beginning of understanding the human compulsion to hear and tell stories, as I learned from the panelists at Why We Tell Stories: The Science of Narrative at the annual World Science Festival. Did our storytelling skills develop as an evolutionary advantage, or were they the side-effect of our evolving into the most social of all species? Are stories practice for how we might deal with extreme situations, or is the act of shaping events into a meaningful package the coping mechanism itself?

The causes we can only conjecture. But the demonstrable effect is that stories are a crucial way we make sense of our world. The MRI at the top reveals that reading stories activates the same network in our brain that helps us to understand other people. Other scientific research shows that the more people read, the more accurately they can interpret people’s facial expressions. What it comes down to is this: Storytelling is a simulation of the social world. Engaging with a story requires imagining another person’s mind. Thus, stories increase empathy, which improves social interactions… which makes us better social beings.

At the heart of all our stories past and present remains a deep, unchanging curiosity about “what people are up to,” a fundamental itch we need to scratch. If stories are simple, primitive, and ancient, as the panelists agreed, what is more exemplary than the genealogical story? After all, the oldest stories, from mythology to the Bible, record both long lineages and involved family history as they grapple with our origins and ultimate fate. And if the whole point of story is to understand ourselves and our interactions, how better to accomplish this goal than through the lives of our forebears, people who are like us and shaped us?

Life is only finite in retrospect; it feels unbounded as we live it, sometimes terrifyingly so. But the stories of our ancestors are life made finite. The ending that death imposes allows us to give their lives an arc and an ultimate meaning that our own lives lack: storytelling as coping mechanism, indeed. And if the value of their lives can persist past death thanks to our efforts, perhaps our ultimate demise need not be the end of our stories, either.

We who do genealogy have long been motivated by the belief that we are our family stories and are improved by this self-knowledge. The research presented in this talk suggests that stories can actually change us. So, the next time a friend or family member mocks your determination to uncover a long-lost family secret, tell them that you are at the cutting-edge of cognitive neuroscience-based self improvement techniques!

Follow

Follow

Pingback: Storytelling: The Ancient Memory Mechanism that Helps Brands Thrive | Edgar, the storyteller