It is the most important revolution in how we read in history: the traditional form factor of books is dramatically altered after centuries. Readers must alter how they read–not only how they physically manipulate these new books, but also how they remember a book’s content in their minds and discuss it with friends. During the time period when the old format gradually supplants the new, there are lots of complainers who feel that the new way debases the reading experience as well as the content itself. “I just don’t read that way!” they protest.

Do you think I’m talking about the rise of e-books?

I’m not — I’m talking about the replacement of scrolls with codexes (books) starting in the first century!

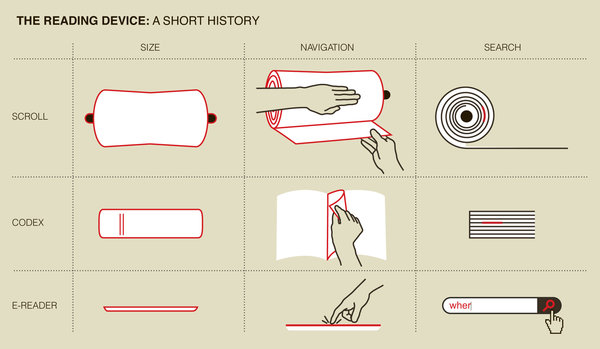

We genealogists know better than most how much history repeats itself, but it’s amazing to think that almost two millennia ago, people struggled to make the switch from one-sided, one-page scrolls to two-sided, many-page books just as we struggle to move from paper to screen. We know why e-books are winning: superior technology. Codexes replaced scrolls for the same reason. The breakdown into pages meant for the first time the reader could easily flip back and forth to different sections and reference passages in a clear way. These advances enabled the early Christians to study and share scripture; it was they who popularized codexes.

Illustration by Joon Mo Kang via

Unfortunately, the e-book format reverses some of this progress. On an e-reader, as in a scroll, it’s very difficult to read non-linearly. This reason is partly why I am one of the hold-outs still without an e-reader. I have rituals for how I mark my place, identify my favorite passages, and sometimes let myself skip ahead (bad!). Instead of buying art, I line my walls with shelves of books, and when one catches my eye, I pull it down to skim my favorite parts. How does any of this happen with an e-reader?

E-readers clearly win for making books more accessible, affordable, and portable. But do they advance the actual experience of reading as codexes did? Search engines and hyperlinks are useful, but surely I’m not just a curmudgeon when I say that the inability to flip through pages is more than the loss of my life-long habits, but a set-back for how we consume and absorb content?

In the first century Pliny wrote, “our civilization…[depends] very largely on the employment of paper,” upon which “the immortality of human beings depends.” Though short-sighted about paper, he hits a kernel of truth in the transmission of knowledge. Four centuries later Cassiodorus says it better. A papyrus scroll “keeps a faithful witness of human deeds; it speaks of the past, and is the enemy of oblivion…There discourse is stored in safety, to be heard for ever with consistency.” This is the principle that matters most: a witness that transcends time. So long as we maintain that — whether via ink or pixels — we’ll progress. The Greeks only read linearly, and look how they advanced human knowledge!

Follow

Follow

I just saw found your website through Geneabloggers. Welcome to Geneabloggers.

Regards, Jim

Genealogy Blog at Hidden Genealogy Nuggets

Thank you so much for the welcome! I hope you will keep reading! I’ve added your blog to my feed reader, too.