Two years and few days ago I published a blog post comparing the modern transformation wrought by e-readers to the ancient transformation by the codex (book). I was fascinated by the ways in which the physical changes in how we interact with the printed word led to mental changes in how we process the recorded information itself.

Two years and few days ago I published a blog post comparing the modern transformation wrought by e-readers to the ancient transformation by the codex (book). I was fascinated by the ways in which the physical changes in how we interact with the printed word led to mental changes in how we process the recorded information itself.

While reading Moonwalking with Einstein, I discovered that there was an even earlier and more significant transformation in how we preserve information: the very creation of writing itself! Foer explains,

In Plato’s Phaedrus, Socrates describes how the Egyptian god Theuth, inventor of writing, came to Thamus, the king of Egypt, and offered to bestow his wonderful invention upon the Egyptian people. “Here is a branch of learning that will…improve their memories,” Theuth said to the Egyptian king. “My discovery provides a recipe for both memory and wisdom.” But Thamus was reluctant to accept the gift. “If men learn this, it will implant forgetfulness in their souls,” he told the god. “They will cease to exercise their memory and become forgetful; they will rely on that which is written, calling things to remembrance no longer from within themselves, but by means of external marks. What you have discovered is a recipe not for memory, but for reminding.”

Of course, 2500 years later, we have been so inculcated in the ways of the written word that it’s hard to understand Socrates’ point of view. Everything about how we remember is shaped by living in a culture of near-universal literacy. Our ancestors, who relied upon oral traditions, might have had an easier time sympathizing. Whether because they were illiterate or because their society’s definition of literature didn’t cover personal concerns, they took part in a long chain of oral storytelling by necessity.

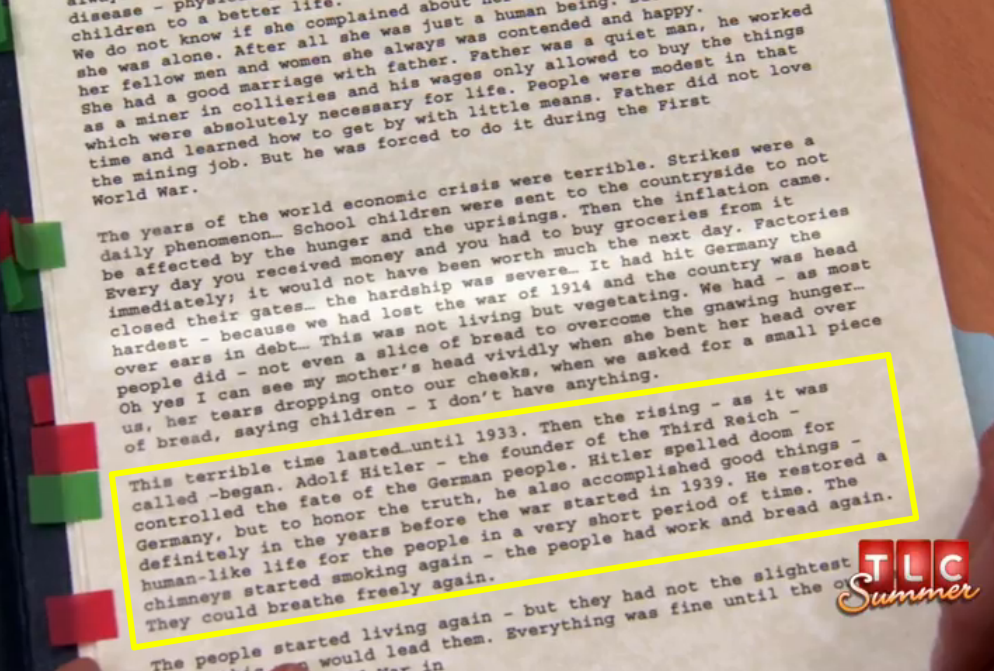

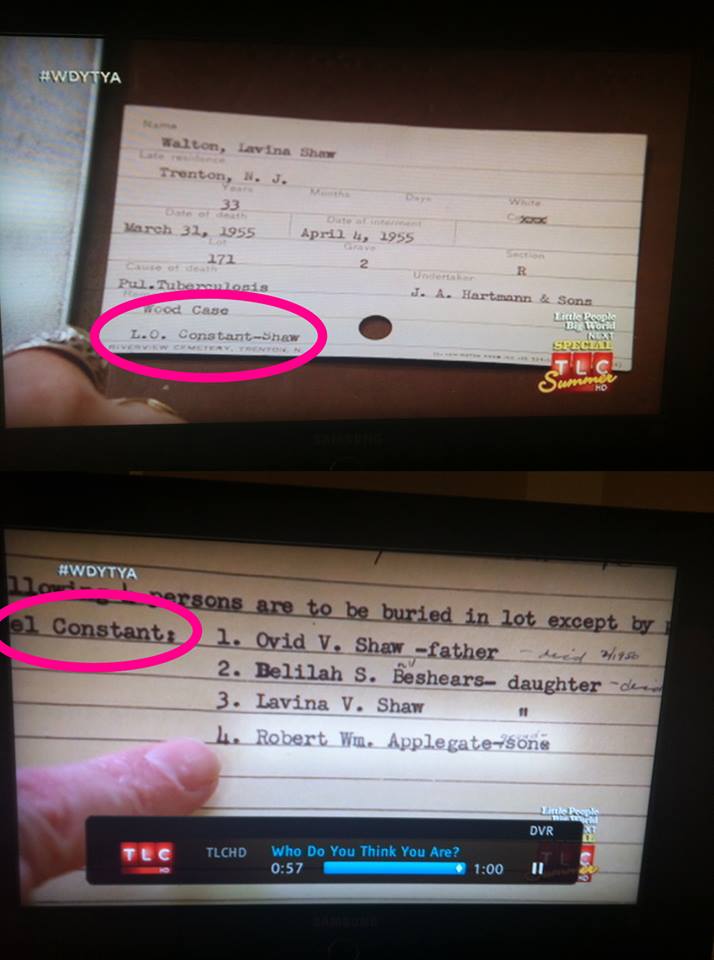

It was the encounter with modernity that eliminated this chain in many cultures. There was a sense that oral history was primitive and written history superior, but looking back we now know that not to be the case. The irony that Socrates’ sentiments would have been forgotten had not his students “put his disdain for the written word into written words” points to the complicated relationship between the two. Socrates lived during the many-generation flowering of Greek philosophy and knew his students would continue his teachings as had been happening since long before his time. During such periods of continuity when people have the luxury of listening and repeating, oral history functions properly. But written history is critical during the periods of discontinuity when the chain breaks down, as happened centuries after Socrates, when first Greek culture and then much of Western philosophy faded away. For families like mine where the discontinuity of immigration came within the past century or two, we’re in the odd position of both ruing the loss of family storytelling as our grandparents or great-grandparents experienced it, and being in the midst of a new period of continuity in our families where this kind of storytelling could thrive once more… if only we knew the stories they did.

But in family history today, you might protest, we emphasize the important of both. True, everyone agrees that recording one’s elders is critical, and technology abounds to make it easy to do so. But this isn’t what Socrates meant. To paraphrase his words, we still rely on what is recorded — now audio and video in place of text. Yes, so much more comes alive when we can hear and see our loved ones reflect on the world they knew, but, as Socrates cautioned, these are crutches for memory, too. His warning is still relevant millennia later: Will the next generation use our writings and recordings as a substitute for doing the real work of remembering themselves? How can we create a culture in our families where don’t just hand off our papers and tapes, but pass down traditions personally?

Follow

Follow

It took me a few years, but recently I finally got around to reading the bestseller

It took me a few years, but recently I finally got around to reading the bestseller