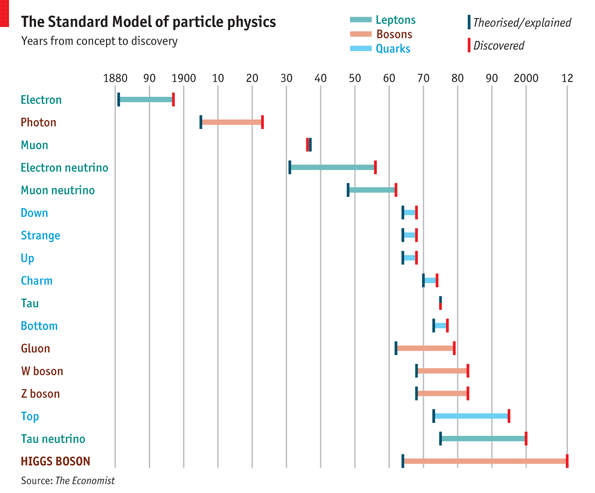

Yesterday morning while we Americans were waking up to a national holiday, our European friends kicked off a world-wide celebration when they announced promising evidence that the Higgs boson, a.k.a. the “God particle,” exists. (Please don’t tune out just because I’ve mentioned physics; this post won’t teach you a thing, I promise. But if you’re curious, this video is awesome.) Of all the articles and analyses I read, The Economist‘s amazing timeline, “Worth the wait: A timeline of the Standard Model of particle physics,” most impressed me with the huge scale of this achievement 131 years in the making!

A hundred and thirty one years… Look at the timeline: where was your family when the electron was predicted, kicking off this amazing journey? For me the year 1881 stands out for the assassination of Czar Alexander II, which unleashed a wave of pogroms that affected two-thirds of my forebears. At that time all my family — the one branch that had already immigrated to the U.S. — and all the rest still in Eastern Europe — were just trying to survive and likely had no time for or knowledge of such scientific developments. It would be decades until they did. My father, born when only four particles were known and three discovered, may have been the first.

A hundred and thirty one years… Look at the timeline: where was your family when the electron was predicted, kicking off this amazing journey? For me the year 1881 stands out for the assassination of Czar Alexander II, which unleashed a wave of pogroms that affected two-thirds of my forebears. At that time all my family — the one branch that had already immigrated to the U.S. — and all the rest still in Eastern Europe — were just trying to survive and likely had no time for or knowledge of such scientific developments. It would be decades until they did. My father, born when only four particles were known and three discovered, may have been the first.

Meanwhile, progress in particle physics, as you can see from the timeline, was initially slow until the 60s. You know all those jokes, “When I was a kid, Pluto was a planet?” My father likes to point out that even when he started work as a physicist, no one had any idea quarks were out there. There wasn’t even a Standard Model, just a “particle zoo” no one could sort out. But by the time my sister and I came along and my father started teaching us particle physics on the play chalkboard in the basement, the Standard Model had taken its modern form, with the vast majority of it having been discovered. (Classroom pedagogy, however, hadn’t caught up: when I told my sixth grade science class that protons and neutrons weren’t fundamental particles, it didn’t end well. And don’t ask about the time I told my 9th grade physics class there was no such thing as gravity…)

My father raised me equally on family history and physics theories. He taught me enough of our background to appreciate our family’s struggle to realize the American Dream, and were it not for him, I could not recognize that it was others who made it possible for me to have idled the day away yesterday reading all about the meaning of the Higgs data without fear of starvation or persecution. What an amazing journey — my family’s and the world’s. Genealogical discoveries don’t heal family rifts, and particle physics breakthroughs don’t mend our broken world, but they both pull us out of the mire of our day-to-day to marvel at the improbability of our being here at all.

Follow

Follow