As genealogists broaden their interests beyond their most illustrious forebears to include their least, specialized kinds of records must be sourced to flesh out the story of people who were overlooked in their own time. The descendents of enslaved Americans, who never even had birth certificates, marriage records, or proper tombstones, face a rather extreme version of this challenge. But personal records do survive in unexpected corners. One underutilized resource that provides insight, and perhaps inadvertent dignity, to early American slaves is a collection of runaway slave ads reprinted in Graham Hodges‘ 1994 book Pretends to Be Free: Runaway Slave Advertisements from Colonial & Revolutionary New York & New Jersey. The “top of an ill-defined iceberg,” the 753 fugitive slaves described in these ads stand out as individual personalities representing a forgotten and largely unmemorialized group.

As genealogists broaden their interests beyond their most illustrious forebears to include their least, specialized kinds of records must be sourced to flesh out the story of people who were overlooked in their own time. The descendents of enslaved Americans, who never even had birth certificates, marriage records, or proper tombstones, face a rather extreme version of this challenge. But personal records do survive in unexpected corners. One underutilized resource that provides insight, and perhaps inadvertent dignity, to early American slaves is a collection of runaway slave ads reprinted in Graham Hodges‘ 1994 book Pretends to Be Free: Runaway Slave Advertisements from Colonial & Revolutionary New York & New Jersey. The “top of an ill-defined iceberg,” the 753 fugitive slaves described in these ads stand out as individual personalities representing a forgotten and largely unmemorialized group.

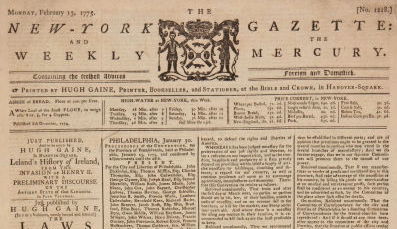

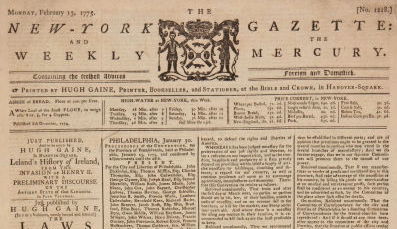

Take, for instance, the ad placed in the loyalist New York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury for Betty, a rare example of a female runaway, who left her master while New York was under British occupation in 1777.

Take, for instance, the ad placed in the loyalist New York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury for Betty, a rare example of a female runaway, who left her master while New York was under British occupation in 1777.

A NEGRO WENCH, RUN-AWAY, supposed to Flatbush, on Long-Island, where she was lately purchased of Cornelius Van Der Veer, jun. is about 2[ ] years old, call’d BETTY, can speak Dutch and English, is of a stubborn disposition, especially when she drinks spirituous liquors, which she is sometimes too fond of; is a pretty stout wench, but not tall, smooth fac’d and pretty black; ’tis probable she may be conceal’d in this city. Whoever harbours her will be prosecuted, but such as give information to Wm. Tongue, her owner, in Hanover-Square, shall receive FIVE DOLLARS with thanks. She usually wore a striped homespun pettycoat and gown.

Here’s the context lacking from the ad: Much of the city had burnt in a massive September 1776 fire, and the Van der Veer family, her former owner, was particularly reeling: several of its men were serving in what was to become known as the Continental Army, and one Van der Veer, a military surgeon, may have already been captured. This information, readily available to any history buff, likely explains why Betty was sold.

But the biographical details about Betty are unique to this source. Though the description of her character is tainted by the frustrations of her owner, it’s also likely the only assessment of her personality that exists. Between the lines one can detect her positive qualities — her opportunism, commitment to the family she was taken from, and her determination to gain her freedom — as well as clues with research potential. For example, the fact that she is bilingual in Dutch and English indicates that she must have deep connections to her destination, Flatbush, as this agricultural corner of Brooklyn retained its Dutch character for generations after Peter Stuyvesant’s surrender in 1664.

Another ad, also in a 1777 issue of the Gazette, seeks the return of 25 year old Harman. In it, one can almost sense the indignation of the person writing the ad after Harman’s second disappearance.

TEN DOLDARS Reward. LEFT Brigadier General De Lancey’s service, from his farm at Bloomingdale. a negro fellow named HARMAN, of a yellowish colour, broad face and shoulders, hollow back, big buttocks, and remarkable strong well shaped legs, with a very large foot, is about 25 years of age, understands farming. Had on a Dutch Thrumb’d cap, a blue sailors jacket, speckled or white shirt, good trowsers and shoes, with a spare buckskin breeches. This is his second elopement, and by his dress may induce masters of ships to entertain him, who are requested to deliver him to New-York goal. Whoever takes him up shall have the above reward paid by General DeLancey, the printer, or Mr. Joseph Allicocke.

Harman’s fine dress was atypical — most runaways had only the standard slave attire of buckskin britches and tow cloth shirts. As the ad notes, this advantage gave him an unusual form of cover… or is the writer insinuating something more about his character and intentions?

It would have been well-known to readers that Harman’s owner, the notorious loyalist General Oliver DeLancey, was away at the front with the regiments he personally financed, and Joseph Allicocke, another prominent loyalist, was responsible for collecting him. It turns out Harman’s timing was prescient as well as opportunistic: the DeLancey manor house was ransacked by patriots a few months later.

Harman and Betty were part of a dramatic increase in the number of runaway slaves during the war. Some even fought for the country’s independence — or against their former masters. The most famous of these is the subject of his own ad: “Run away from the subscriber, living in Shrewsbury, in the county of Monmouth, New-Jersey, a NEGROE man, named Titus, but may probably change his name..” Indeed, Titus, became Colonel Tye, a Loyalist commander who led raids against the Americans. (You can read more about the fate of these Black Loyalists here.)

From these examples one gets a sense of the valuable information that these runaway slave ads can provide genealogists. They are rich in both names and stories; masters, slaves, agents, printers, and locations are all described. More than that, the perverse level of detail in which owners documented their lost property ironically gives us some of the most complete human portraits we have of enslaved Americans. Ads routinely list scars, bad habits, skills with animals, farming, trades, languages spoken, and even musical aptitude (42% of runaways were musicians!). Family and geographical connections are at times made plain, shedding rare insight into a group of people for whom a more traditional paper trail does not exist.

As genealogists we always need to keep in mind that resources are always most useful when used in conjunction with each other. How do these ads compare to family records? Do bills of sales or receipts in ledgers help us paint a broader picture of the lives of both slaves and masters? And what of the family burial ground? If you’re one of the rare genealogists who has been able to trace your enslaved ancestors to the Colonial period, comparing your existing records to these ads might reveal a lost chapter of courage in your family’s history. And for those without a traceable connection to these people, the glimpses into slave culture and masters’ perceptions of their property reveal details about this period that history books too often gloss over.

Though Pretends to Be Free is a difficult and expensive book to purchase, much of it is available on Google Books, and it is held by many large public libraries. Search WorldCat.org to find a copy near you, or your local librarian can help you utilize the interlibrary loan network.

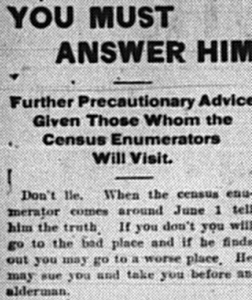

A trove of articles I’ve uncovered from The News-Messenger, the local paper of Homestead, Pennsylvania, sheds some light on these discrepancies from the perspective of the census takers in 1900. It’s clear that everyone understood the odds were against the enumerators to get accurate information, but the paper went to great lengths to ensure that “Homestead will not be found in the [class represented] as obstructing the endeavors of the enumerators to get the exact truth in the information they seek” (5/2/1900). It started by printing the census instructions several times to prepare readers with the list of questions they’d be asked and how to be sure of answering them accurately. In case the instructions weren’t enough, an often hilarious article from May 17, 1900 resorted to dire warnings: Continue reading

A trove of articles I’ve uncovered from The News-Messenger, the local paper of Homestead, Pennsylvania, sheds some light on these discrepancies from the perspective of the census takers in 1900. It’s clear that everyone understood the odds were against the enumerators to get accurate information, but the paper went to great lengths to ensure that “Homestead will not be found in the [class represented] as obstructing the endeavors of the enumerators to get the exact truth in the information they seek” (5/2/1900). It started by printing the census instructions several times to prepare readers with the list of questions they’d be asked and how to be sure of answering them accurately. In case the instructions weren’t enough, an often hilarious article from May 17, 1900 resorted to dire warnings: Continue reading  Follow

Follow

Tomorrow, for the last time until the year 79811, Thanksgiving overlaps with

Tomorrow, for the last time until the year 79811, Thanksgiving overlaps with  TWIN FESTIVALS

TWIN FESTIVALS

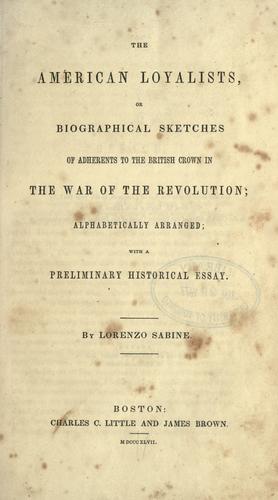

Loyalist genealogical associations began to blossom, particularly in Canada, with the 1847 publication of

Loyalist genealogical associations began to blossom, particularly in Canada, with the 1847 publication of  As genealogists broaden their interests beyond their most illustrious forebears to include their least

As genealogists broaden their interests beyond their most illustrious forebears to include their least Take, for instance, the ad placed in the loyalist New York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury for Betty, a rare example of a female runaway, who left her master while New York was under British occupation in 1777.

Take, for instance, the ad placed in the loyalist New York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury for Betty, a rare example of a female runaway, who left her master while New York was under British occupation in 1777.