Two weekends ago I drove up to my old summer camp to take part in opening a time capsule that twenty years prior the whole camp had gathered to fill. At the time it felt surreal — 2012 seemed impossibly far away. “I don’t think I’ll ever reach the day when I read this,” I wrote myself, but two decades later my letter, damp and moldy, was back in my hands.

Two weekends ago I drove up to my old summer camp to take part in opening a time capsule that twenty years prior the whole camp had gathered to fill. At the time it felt surreal — 2012 seemed impossibly far away. “I don’t think I’ll ever reach the day when I read this,” I wrote myself, but two decades later my letter, damp and moldy, was back in my hands.

Both my past and present selves feared that reading my childhood hopes-n-dreams would be emotional (“You’re probably crying now because I am almost crying as I’m writing this!!!”), but surprisingly, my strongest response came from fellow campers who had a much less personal idea about what they wanted the time capsule to capture. Many listed generic information about camp recorded elsewhere, like names of girls in their bunk, lyrics of songs, Color War themes, and love for traditions and friends. Others deposited camp and cultural artifacts, the ubiquitous clutter of our childhood. The camp-related items, lists and memorabilia alike, recalled activities I spent years enjoying or avoiding. Comic books, toys, and magazines recreated the long-gone world we had grown up in. Every day the world changes imperceptibly, even major shifts we somehow take in stride, so it was disorienting to be faced with the net result of twenty years of change I rarely noticed happening. I had not expected the world of my youth to feel so strange!

We had to explain the dot-matrix printed banner at the top of the picture to recent campers, the oldest of whom were born in the late ’90s.

Perhaps the effect was compounded by the presence of recent camp alumni, all born after the time capsule was sealed. My peers lament how much childhood has been sullied by technology, but the younger alumni’s glimpse of the world just before the Internet made them pity us in return. And yet, the twenty year-old record of songs and friends and traditions I had thought so pointless to include was what collapsed the divide between the older and younger alumni. We recognized that there was an unbroken thread between our camp years and theirs. We cherished the same experiences in two very different times. Our lives suddenly felt familiar to each other.

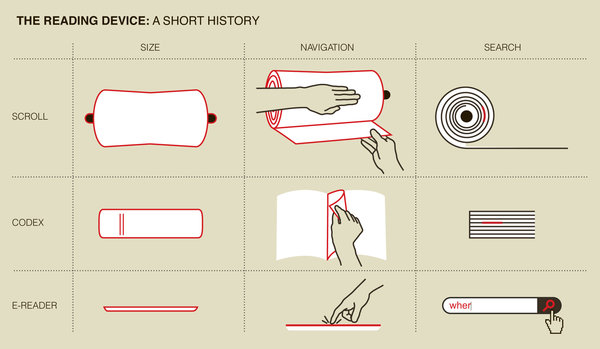

This time capsule covers a small slice of time compared to the centuries we try to leap in genealogy. Rarely do we read records that so self-consciously address the future, but we’re similarly trying to intuit what they’ve captured about the way things were and to connect with people recalled only by small details. It’s easy to get so diverted by dramatic changes in technology, culture, and worldview that we forget that human experience is much the same as it always was (which the richness of literature handles better than the spareness of records). When we set aside the fundamental foreignness of the past and separate changing times from continuous humanity, we’ll recover a lot more of value.

Follow

Follow

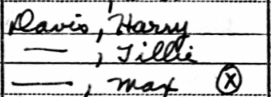

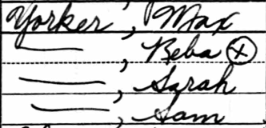

Here is my grandfather with his parents in the 1940 census. What do you think his mother’s name is?

Here is my grandfather with his parents in the 1940 census. What do you think his mother’s name is?

The second time I swabbed my cheek for a genetic test,

The second time I swabbed my cheek for a genetic test,

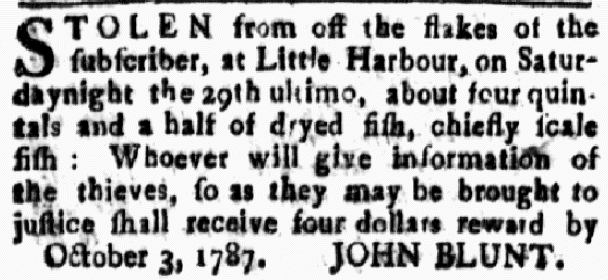

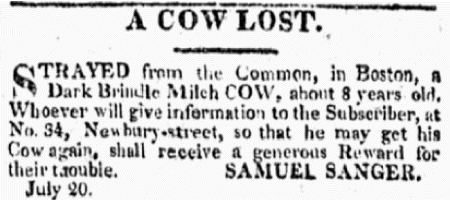

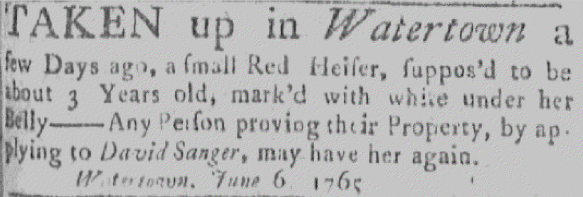

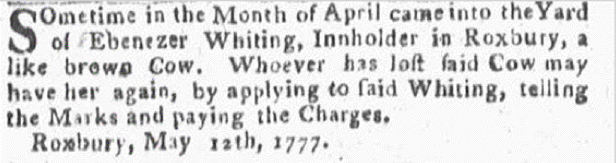

Robert’s ancestors relied upon the newspapers for information about many other kinds of lost items, too, even dead fish:

Robert’s ancestors relied upon the newspapers for information about many other kinds of lost items, too, even dead fish: