The Jewish holiday of Passover, which starts tonight, centers around a highly ritualized dinner called a Seder (“Order”). Most of the Seder is spent reading and discussing the story of the exodus from Egypt as recounted in a book called the Haggadah (“Telling”). As it explains, “All who discuss the exodus from Egypt at length are to be praised.” To that end, everyone is encouraged to ask questions, suggest interpretations, and offer historical or personal parallels to elaborate upon the Haggadah’s version, and indeed, at a lively seder it could be hours before the meal begins. Last year, I introduced how the text of the Haggadah works to incorporate the whole family. This year I want to discuss the section that precedes the recounting of the exodus story: the story of the Four Sons.

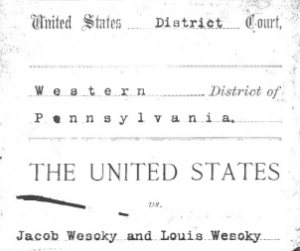

Illustration of the Four Sons by Nota Koslowsky, U.S.A., 1944*

“The Bible speaks about four sons: one wise, one wicked, one simple, and one who doesn’t even know how to ask,” begins the story. Each child asks their version of a question seeking to understand the holiday. The wise one requests the specific details of how the holiday must be observed. The wicked one asks, “What does this observance mean to you?”** The simple one pleads, “What is all of this?” And I think you can all guess about the one who doesn’t know how to ask. In each case the Haggadah instructs how to respond to the child.

This year it’s the wicked son’s question-and-answer that rattles around in my mind. Does the Haggadah represent the intentions behind the wicked son’s question fairly? It focuses on his words “to you,” hearing in them a desire to “[exclude] himself from his people.” It instruct his parents, “Say to him: ‘It is because of what the Lord did for me when I came out of Egypt’ — for me and not for him.” (Exodus 13:8) In other words, scare the wicked child from his ways with a vision of what it really means to be excluded.

My mind catches instead on first part, “What does this mean?” I hear a bewildered child wondering, Here we all are sitting around this table. We spent the past week preparing a holiday feast which we’re not yet allowed to eat because this discussion must happen first. Parents, please tell me why it matters to you that we do this, so I can understand why it should matter to me. What does this observance mean to you? Perhaps the wicked child’s intentions are honest: to be shown a way to connect to this observance happening before him.

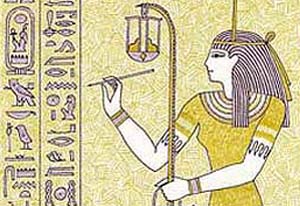

Illustration of the Four Sons from a 1695 Haggadah printed in Amsterdam*

In the wicked child’s not-so-wicked question I find myself thinking back to my own experiences when I first got into genealogy — trying, and initially failing, to convince my own family to care about the discoveries I was making about our ancestors. Their muted reactions to the names, dates, and relationships I was sharing were their own, innocent version of, “What does this mean to you?” Why does dredging up this forgotten family history matter? The failing wasn’t theirs; it was mine. I had to I stop presenting elaborate trees with historical records and start interpreting this raw material in a way that made it relevant to my family. A census gives a snapshot of how our ancestors’ circumstances compared to our own. An immigration record hints at what they endured so we would not. Every detail can change the way a family sees itself if looked at in the larger context of history and society. I had to do more research to learn what these discoveries were really conveying, not just about my ancestors’s lives, but also about their world.

If the wicked son is redeemed by my re-reading of his question, then praise for the wise son must be partially retracted. The wise son asks for details without context where the wicked sons asks for context with no details. Neither can stand without the other, especially not in family history. I failed when I asked my relatives to draw their own conclusions from lists of names and dates and towns, and I failed, too, when I threw out historical tidbits without any orientation, but when I put the pieces together, it was like my family was reading their favorite historical fiction, except the story was true, and its thrust was how they came to be.

At the conclusion of the section about the Four Sons, when the Haggadah starts answering the questions it has posed through these children and in previous sections, it also balances (Biblical) history with the (theological) interpretations that explain its continued relevance. Something in this formula must resonate deeply, since this text has been passed down from generation to generation for nearly two thousand years. Your family history goals may not be quite so ambitious, but, as the Haggadah says, “go and learn” from what has endured.

Happy Passover to those who celebrate it.

* In the illustrations, the sons are in order from right to left (following the direction in which Hebrew is written).

** The literal translation of the Hebrew is, “What [is] this observance to you?” It’s complicated to translate since Hebrew grammar omits the verb in this construction, so the translator’s art must guide choosing words that best capture the intended sentiment. “Mean” is the verb I saw in all the translations I consulted.

Follow

Follow

Two years and few days ago I published

Two years and few days ago I published  It took me a few years, but recently I finally got around to reading the bestseller

It took me a few years, but recently I finally got around to reading the bestseller

Now I’m gearing up to speak in a couple days at NGS in Richmond, VA. My talk, “

Now I’m gearing up to speak in a couple days at NGS in Richmond, VA. My talk, “

Have you heard about Heartbleed? It’s a

Have you heard about Heartbleed? It’s a

Recently I read in Carla Peterson’s impressive

Recently I read in Carla Peterson’s impressive