Today is the day the UN designated International Holocaust Memorial Day. Sixty-eight years ago Auschwitz-Birkenau, the most notorious of the death camps, was liberated. I don’t often have occasion to do genealogical research for this period, but last spring a family friend asked me to research his uncle, Shlomo Israelit. In remembrance of the six million, I’d like to tell you about this one man and his family.

The story the family friend asked me to trace about Shlomo sounded exaggerated: Evidently he was one of the richest men in Latvia because he created and ran the shipping lines that transported timber from the interior of Russia. The only documentation I had for him was a single Page of Testimony from the Yad Vashem website, where his brother had recorded the basic facts of his life. Immediately I turned to Google Maps and saw that Liepaja, the town listed as Shlomo’s residence, was on the coast of the Baltic Sea, which certainly fit with the profession his nephew recollected. Did any other information about Shlomo survive?

The only online destination I knew of to learn more was the JewishGen Latvia Database, one of a number of such online databases with a very haphazard collection of region-specific records. I’ve spent more time than I care to admit in such databases and have mostly come up empty-handed. As this database was the one and only lead I had to go on, with some nervousness I typed in Shlomo’s last name into the search form. The results listed Israelits in nine separate record collections, which was not surprising, but were any of these “my” Israelits? The first eight were not. But the name of the last search result was promising: Liepāja Holocaust Memorial Wall. I clicked through and found these names:

- Salman Israelit, who died at 53 in Stutthof, Germany (Salman is a Yiddishized version of Shlomo, but I will stick with Shlomo, as that is the name that his brother recorded on the Page of Testimony).

- Eta Israelit, who died at 48 in Riga, the capital and largest city in Latvia, which is 200 km from Liepaja (the Page of Testimony lists Schlomo’s wife as Edit)

- Muse Israelit, who died in Liepaja at age 38

- Isak Israelit, who died in Liepaja at age 11

- Minna Israelit, who died in Liepaja before she even turned 1

Here were Shlomo and his wife and three other relatives – children? Grandchildren? Although this information added little to what I already knew, I was consoled to learn that on 6/9/2004 a memorial wall containing the names of Shlomo, his family, and 6,423 other Holocaust victims from Liepaja was dedicated in the town’s Jewish cemetery (see pictures of the wall here). An entire website memorializing the Jews of Liepaja murdered in 1941-1945 detailed the modern efforts to memorialize the destroyed community. Here is what I read about how the Holocaust took place in Liepaja:

About 7100 Jews lived in Liepaja, Latvia on 14 June 1941. About 208 were deported to the USSR that day, a few hundred fled to the USSR after Germany attacked the USSR on 22 June 1941, and most of the remaining ones were killed during the German occupation that began on 29 June 1941. Most men were shot during the summer and fall; at first near the lighthouse, then on the Naval Base, and from October 1941 on in the dunes of Shkede north of town. Women and children were largely spared until the big Aktion of 14-17 December, 1941, when 2749 Jews were shot. Killings continued in early 1942, and by the time the ghetto was established on 1 July 1942, only 832 Jews were left.

The website includes graphic pictures of the Aktion of mid-Deecmber. I could not believe what I was seeing–families queuing up, removing their clothes, and finally, standing on the edge of a deep pit with a pile of bodies clearly visible at its bottom. There are close-up shots of people moments before their death, who know that it is death and only death that awaits them. They are looking at their family, friends, and neighbors at the bottom of a pit. They know they will soon join them in that pit…

Was I looking at the Israelits?

A German officer named SD Oberscharführer Sobeck (rank of staff sargent in the security service) captured these horrible images. His fellow officers gave the orders to the Jews to undress on the dunes and run around naked in the freezing cold for their amusement, and this man stuck his camera in their faces. He knew exactly what he was doing. He even had the presence of mind to record only the Latvian policeman guarding the Jews and not the Germans actually in charge.

(For context: Large-scale massacres like these were how the Germans began their destruction of the Jews in the territories they conquered in the east. Mobile killing units called Einsatzgruppen, “task forces,” went from town-to-town rounding up the Jews and shooting them en masse. One million Jews were killed this way from 1939-1942. This method of killing Jews turned out to be inefficient and demoralizing for the Germans; it was phased out in favor of the gas chambers of the extermination camps whose names, like Auschwitz, have become synonymous with the horror.)

Returning to the chronology, the website concludes with how Liepaja became Judenrein and the fate of its remaining residents:

The ghetto was closed on 8 October 1943 when the survivors were taken to Riga. Young adults were generally spared, but in the next few months older people and women with children were killed locally or in Auschwitz. When the Red Army approached Riga in the summer of 1944, the survivors were sent to the Stutthof concentration camp near Danzig in several transports, from August to October 1944. Many died in the increasingly brutal conditions of this camp, especially on death marches in early 1945, and only 175 survived. Of the deportees and refugees to the USSR, many perished, but some 300 survived. (source)

The site explains that “of the 6500+ Liepaja Jews who perished in WWII, only about 1500 have so far been recorded at Yad Vashem.” Shlomo Israelit was fortunate to have a brother to remember him; the author of the Liepaja site worked for three years to recover the lost names and now has information on 93% of all Liepaja Jews. For Shlomo and his family, I found:

- Salman and Eta Israelit: He was a merchant (again, consistent with the nephew’s information). He died 10/1/1944 in Stutthof. She died in Riga in November 1943.

- Their daughter and son-in-law, Mira and Josef Pasternak: She died in Auschwitz in November 1943 at the age of 22. He was murdered in Liepaja in 1941 at the age of 22. Their son, Deo Pasternak, died in Auschwitz in 11/3/1943 at two-and-a-half. A survivor recalls that Eta cared for Deo.

- Muse Israelit: From the information given, it is unclear how she is related to Shlomo. Her children are the Isak and Minna I found earlier. She may have been unmarried. All three died in Liepaja in 1941.

With the historical chronology I copied above, we can now place the gradual destruction of the Israelit family into context. Josef Pasternak may have been one of the men killed in the summer after the German occupation began. Muse and her children were likely killed in one of the big Aktions later that year, maybe in the one the German officer photographed. The rest became part of the ghetto established in Liepaja and even survived long enough to be transferred to the Riga ghetto. Eta died shortly after being transferred to Riga. Her daughter and grandson died around the same time in Auschwitz. Shlomo outlived all of them; three-quarters of a year after he lost the last of his immediate family, he was transferred to the Stutthof camp and died shortly thereafter.

And that is the story of how the Nazis murdered the Israelit family from Liepaja. They lived, prospered, suffered, and died, and while I knew more about their deaths than their lives (and exceedingly little of either), their names were well-enough preserved so that I, a stranger to them and their family, could tell their surviving family something it turned out they didn’t already know. I wrote up what I found, emailed it to the family friend, and stepped away from the computer, happy that against the odds I had found any information at all on his uncle.

***

But the story doesn’t end there. It often happens in genealogy that you think you’ve read and absorbed a record, but when you come back to it little while later, you see something you can’t understand why you didn’t notice before. If you clicked through the links above, maybe you noticed these comments on Salman’s record that I overlooked at first: “works at German commandanture,” “Chairman of Judenrat.”

Chairman of the Judenrat?

And this is where Shlomo’s story passes beyond mere genealogical records of a life into the historical records of a life that impacted other lives.

From the yizkor book for Liepaja (a yizkor book is a published tribute by survivors to the destroyed the community they came from; the number of such books is in the thousands):

“In spite of overcrowding in the [Liepaja] Ghetto houses, the inmates led an orderly life which was mostly due to the devotion of Mr. Israelit, a senior Jewish functionary in the town, who was assisted by Mr. Kagansky, the lawyer.”

From the St. Petersburg Times:

“The Judenrat members–businessman Zalman Israelit and lawyer Menash Kaganski–were on good terms with [the German commandant] Kerscher and generally managed to arrange lenient treatment of offenders. For this purpose they sometimes bribed him with items such as fur coats, jewelry, or gold coins (contributed by residents), but apparently Kerscher often passed part or all of the bribe on to his superiors to buy their acquiescence. The Judenrat enjoyed the respect and trust of the ghetto residents.”

From a history of Latvia’s Jewish community on the website for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Latvia:

“Israelit and Kagunsky, the leaders of the ghetto’s Council, arranged for a synagogue, a medical centre and a library.”

This was Shlomo Israelit, a businessman who became the leader of his community under the most harrowing circumstances possible–whose house was burned down, whose friends and family were massacred on the sand dunes overlooking the sea where he had made his fortune, but who held himself together well enough to protect his surviving townsmen as best as he could. “The ghetto of Liepāja had slightly better conditions if compared to those in the ghettos of Riga and Daugavpils,” Wikipedia notes in an entry that mentions Salman’s role. This is the difference Shlomo helped to make before he was sent to his death. I was asked to research a spectacularly wealthy businessman and instead found a brave leader.

***

Shlomo’s position as head of the Judenrat certainly supports the idea that he was the leading Jewish citizen in the town prior to the occupation, but of course, you want to know if the story that he was so fantastically wealthy was true? Though there is no reason to doubt his nephew’s recollection, I didn’t pursue the research to prove it. Had I been related to him, I would have wired money to a Latvian researcher to take a look at these tantalizingly-named records, which I found listed in a guide to Jewish materials stored in the Latvian State Historical Archives:

S. Heifez and Z. Israelitin Forestry and Trade fellowship (Riga)

Archival fund: 6520. 1926–1932. Files: 13.

General ledger; rescontro; memorial books; balance.

(Note that Salman is sometimes spelled with a Z.)

Had I been related to him, I would also have someone review the other, more general records in the Latvian archives. The list of merchants in Liepaja in particular could be useful. The birth, marriage, death, military, census, and passport records for the town could flesh out Shlomo’s family tree. This information is for the family to recover, if they wish. But likely a good deal more about Shlomo’s survives out there.

***

Shlomo Israelit may be the one of the six million I’ve spent the most time thinking about, but still I don’t know him. How could he cultivate a positive relationship with the Germans after they murdered almost 90% of his community? Did he believe he could save the remnant? Did he think that the wealth and prestige he accumulated before the war would protect him from sharing the fate of other Jews?

I’ve thought about his brother, too, who survived, who moved to Israel and woke up one day and went to Yad Vashem to submit four Pages of Testimony… for his brother Shlomo, his sister-in-law, and his niece… and for his other brother, Moshe, who died in Wilno, Poland…

There are limits to what research and even memory can reckon with. These are lives we cannot possibly understand. But we can make sure they are not forgotten.

Follow

Follow

The central tradition of Passover, which starts tonight, is for families to gather together for a festive meal called a

The central tradition of Passover, which starts tonight, is for families to gather together for a festive meal called a

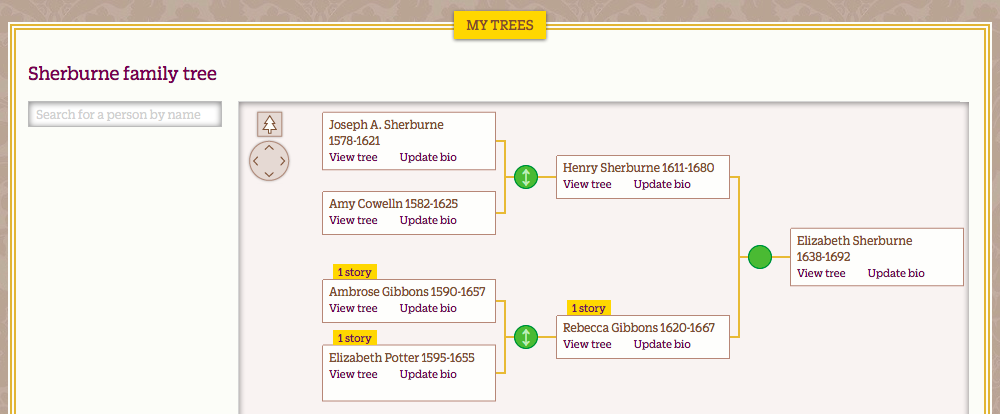

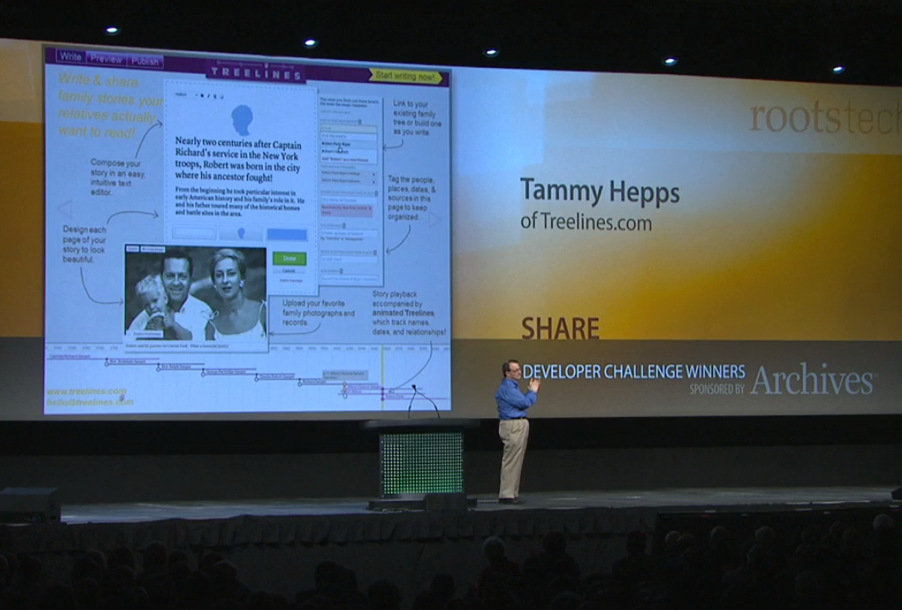

Since last year we’ve been building a family storytelling platform that is going to rock the genealogy world. We’re so excited to unveil it at RootsTech next week — not only to get your feedback after you start using it, but also to read the family stories you share! We’ve already gotten some early validation — Treelines is a finalist for the RootsTech Developer Challenge! As a result, we’ll be demo’ing Treelines Friday afternoon as part of the finalist showcase.

Since last year we’ve been building a family storytelling platform that is going to rock the genealogy world. We’re so excited to unveil it at RootsTech next week — not only to get your feedback after you start using it, but also to read the family stories you share! We’ve already gotten some early validation — Treelines is a finalist for the RootsTech Developer Challenge! As a result, we’ll be demo’ing Treelines Friday afternoon as part of the finalist showcase. Select jobs my family has performed in New York City:

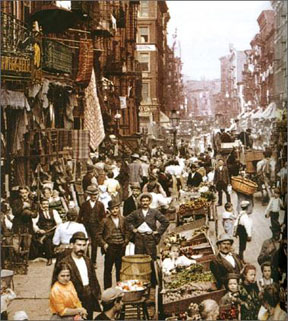

Select jobs my family has performed in New York City: