Eager Americans tearing down the Union Jack (nailed up to a greased flagpole by the petulant Lobsterbacks) on Evacuation Day. In subsequent commemorations boys would compete to perform this feat themselves!

In the U.S. late November has long been defined by the Thanksgiving holiday and its message of gratitude. But in New York for the first half of our history the defining holiday of November commemorated not this 1621 Pilgrim harvest feast, but an arguably more seminal moment in the country’s establishment: the long-overdue evacuation of the British from New York City in 1783, more than two years after the Revolutionary War’s last major engagement at Yorktown. It wasn’t just soldiers who evacuated on that day, though. 1,500 Loyalist civilians, the last of a months-long exodus that may have numbered 40,000, departed as well. We know how the story continues for the Patriots who built our country. But what of the evacuees, who risked everything simply for their desire to live under the same form of government that had been in place for generations?

Their story begins at the start of the war, when the British had conquered New York in August 1776. Shortly thereafter, a huge and mysterious fire destroyed much of the city. Of those who remained in town, those with Patriotic leanings were left in the slums of the “Tent City,” while British officers and prominent Loyalists occupied the choicest residences, regardless of ownership. As a result, after the British defeat at Yorktown in 1781, New York City was the most obvious destination for Loyalists from across the thirteen former colonies. But Patriot New Yorkers returned in droves, and the passage of 1783 Trespass Act gave them a legal pathway to make claim on properties utilized by Loyalists during the war years. Patriot claimants were even indemnified against counter-suits by known Loyalists! Add to the mix thousands of nervous African Loyalists, whose freedom was unclear, and an unknown number of bounty hunters, and you’ll understand how occupied New York City became increasingly chaotic as the peace negotiations in Europe dragged on.

An honorable Redcoat? Carleton freed the slaves who fought with the British and safely evacuated Loyalists.

After numerous brawls and a few coordinated attacks against the hated Tories, British General Sir Guy Carleton declared it his intention to protect the life and property of loyal subjects, and he wouldn’t relinquish the city until his job was complete. He helped establish a joint Board of Claims, the first in a long list of ways Loyalists would attempt to win reparations for their lost property over the next fifty years. He also remained steadfast against General George Washington’s objections to freeing the slaves who had run away from their owners when the British promised emancipation to any who would fight against the Americans. And during that last summer of the occupation, the British government gave free passage to Loyalists to other ports in the empire, primarily Canada — a promise that flabbergasted those in charge of the retreating military’s logistics! In the end approximately 40,000 Loyalists, including 3,500 Black Loyalists, were evacuated safely to Canada or Nova Scotia.

Washington’s triumphal entry into NYC on Evacuation Day.

All of this is a lot to take in! Americans who hated the Declaration of Independence…a New York teeming with enemy soldiers…our most heroic Founding Father tarnishing his reputation to keep men who risked their lives for their own freedom enslaved. Also unexpected for students of American history is the pride Canadians take in their Tory forebears:

United Empire Loyalist monument in Hamilton, Ontario. The accompanying plaque reads:

This Monument is Dedicated to the Lasting Memory of The United Empire Loyalists who, after the Declaration of Independence, came into British America from the seceded American Colonies and who, with faith and fortitude, and under great pioneering difficulties, largely laid the foundations of this Canadian nation as an integral part of the British Empire.

Neither confiscation of their property, the pitiless persecution of their kinsmen in revolt, nor the galling chains of imprisonment could break their spirits, or divorce them from a loyalty almost without parallel.

“No country ever had such founders — no country in the world — no, not since the days of Abraham.” — Lady Tennyson

Proudly Tory Shelburne, Nova Scotia, also the site of race riots against Black Loyalists in 1784. Half of this group took the opportunity offered by the British government to begin anew in Sierra Leone in 1792.

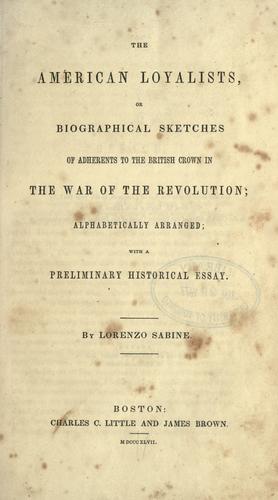

Loyalist genealogical associations began to blossom, particularly in Canada, with the 1847 publication of The American Loyalists, or, Biographical Sketches of Adherents to the British Crown in the War of the Revolution by Lorenzo Sabine, a New England businessman and politician with no familial connection to Loyalism. Coining the term United Empire Loyalists, Sabine invigorated descendents of Loyalists to honor their ancestors and acknowledge the hardships they endured. Sabine’s work is now regarded as a starting point in Loyalist genealogy. It gives the most attention to those prominent men who often managed to transfer their wealth and/or power from one imperial outpost to another: an example is Charles Inglis, the rector of New York’s famous Trinity Church and author of The Deceiver Unmasked; or, Loyalty and Interest United: in answer to a pamphlet entitled Common Sense (as in, Thomas Paine’s revolutionary pamphlet Common Sense), who became the first Bishop of Nova Scotia in 1787.

Loyalist genealogical associations began to blossom, particularly in Canada, with the 1847 publication of The American Loyalists, or, Biographical Sketches of Adherents to the British Crown in the War of the Revolution by Lorenzo Sabine, a New England businessman and politician with no familial connection to Loyalism. Coining the term United Empire Loyalists, Sabine invigorated descendents of Loyalists to honor their ancestors and acknowledge the hardships they endured. Sabine’s work is now regarded as a starting point in Loyalist genealogy. It gives the most attention to those prominent men who often managed to transfer their wealth and/or power from one imperial outpost to another: an example is Charles Inglis, the rector of New York’s famous Trinity Church and author of The Deceiver Unmasked; or, Loyalty and Interest United: in answer to a pamphlet entitled Common Sense (as in, Thomas Paine’s revolutionary pamphlet Common Sense), who became the first Bishop of Nova Scotia in 1787.

Today there’s a lot more you can read about these families, whether you are researching your own roots or fascinated by this lost chapter in U.S. history. Genealogists such as Gregory Palmer and Paul Bunnell have updated and vastly expanded Sabine’s work, taking more systematic and scientific approaches to tracking all Loyalists, regardless of economic circumstances, political stature, gender, or race. Between them they have mined tens of thousands of Loyalists claims and found evidence of Loyalist migrations to the furthest corners of the British Empire. Historian Philip Ranlet provides remarkable depth to New York loyalism in particular, outlining the continuum of these British subjects’ political activism, which ranged from passive obedience, to militant Toryism via regiments that weeded out disloyal neighbors and took on Continental soldiers (loyalist New York City troops alone made up four battalions!). Further complicating the range of Tory identities, Richard Ketchum argues that many New York Loyalists began as active reformers against onerous Parliamentary acts in the 1760s, but ultimately drew the line at full-fledged revolt. And Black Loyalists get special attention from James Walker, who researched their arduous journeys from the 13 colonies to Nova Scotia and onto Sierra Leone in a protracted effort to gain true freedom.

There is so much in this history that complicates the straightforward narrative we Americans are typically taught about the founding of our nation. Like Evacuation Day, Thanksgiving certainly comes with its own troubling questions — the harmony between Pilgrims and Native Americans did not last much beyond that one meal, as is well known — but regardless of which holiday we observe this week, nothing is more American than thinking critically about our history to make a better world. Let’s be grateful we live in a country where we can do so!

Follow

Follow

As genealogists broaden their interests beyond their most illustrious forebears to include their least

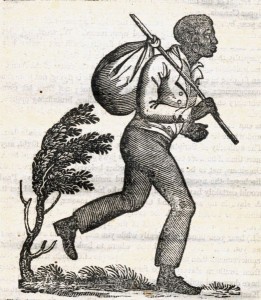

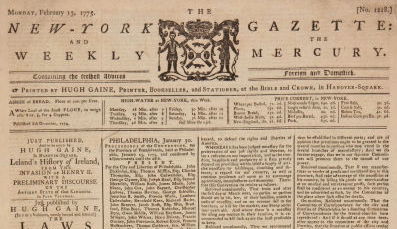

As genealogists broaden their interests beyond their most illustrious forebears to include their least Take, for instance, the ad placed in the loyalist New York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury for Betty, a rare example of a female runaway, who left her master while New York was under British occupation in 1777.

Take, for instance, the ad placed in the loyalist New York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury for Betty, a rare example of a female runaway, who left her master while New York was under British occupation in 1777.

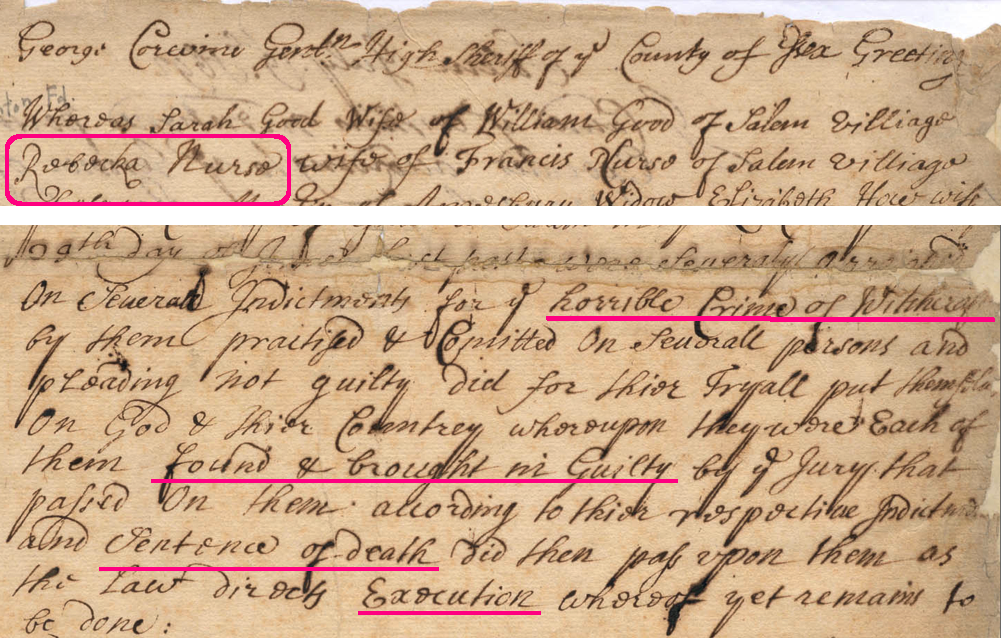

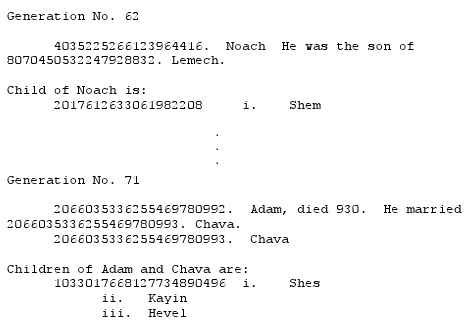

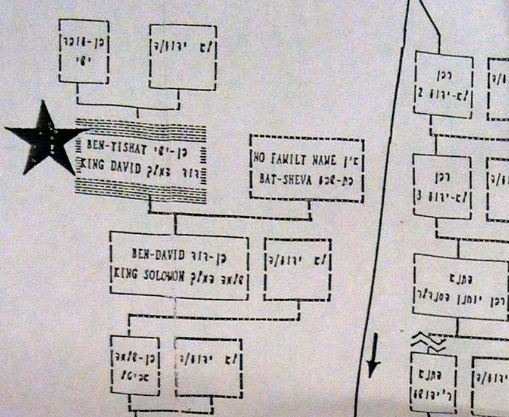

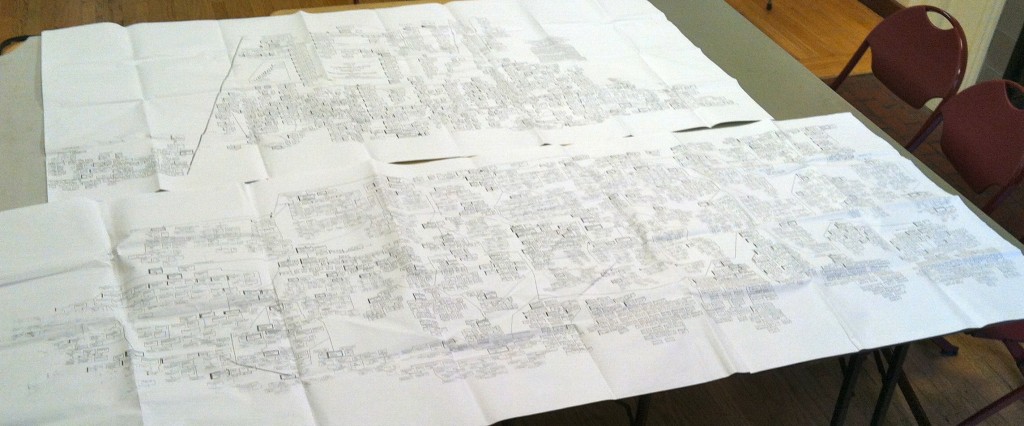

So now you understand how my friends M. and Dan can trace themselves back to Adam, but what about me? I have no connection to these rabbinical dynasties that I know of. But when I found my

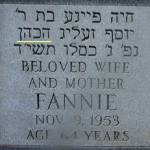

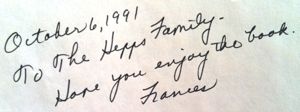

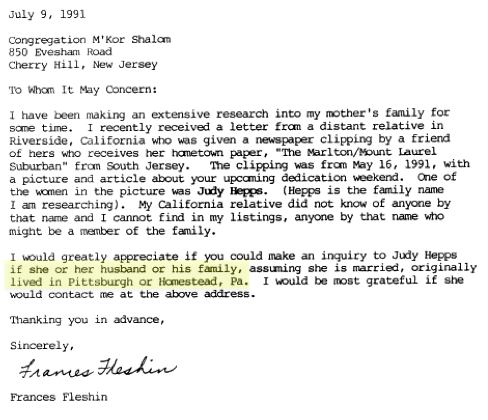

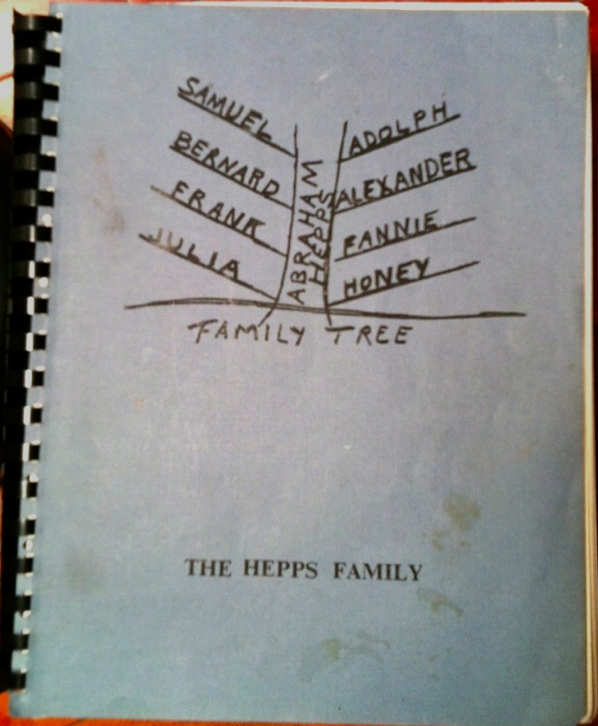

So now you understand how my friends M. and Dan can trace themselves back to Adam, but what about me? I have no connection to these rabbinical dynasties that I know of. But when I found my  The frustration of being the genealogist in my family is that I’m always the one reaching out to relatives, close and distant, to learn more about our family. I long for the reverse: to be found myself by a relative who has the stories, photographs, and connections to break through my toughest brick walls or add much-needed color to the barest areas of my tree. But I sometimes overlook that twenty-one years ago that did happen to me:

The frustration of being the genealogist in my family is that I’m always the one reaching out to relatives, close and distant, to learn more about our family. I long for the reverse: to be found myself by a relative who has the stories, photographs, and connections to break through my toughest brick walls or add much-needed color to the barest areas of my tree. But I sometimes overlook that twenty-one years ago that did happen to me:

When I found my great-grandfather in the

When I found my great-grandfather in the